What did the Mayans eat for food?

Agriculture and arboriculture produced lots of food, but thousands of Mayan people also gathered fruits, vegetables, roots, and other edible plants from their kitchen gardens and from forests (of wild plants).

Most of these edible native foods of the Mayan people have been replaced by commercial crops and junk food in plastic bags. It is a human ethical courtesy to assist people learn what foods are available in the fields and forests.

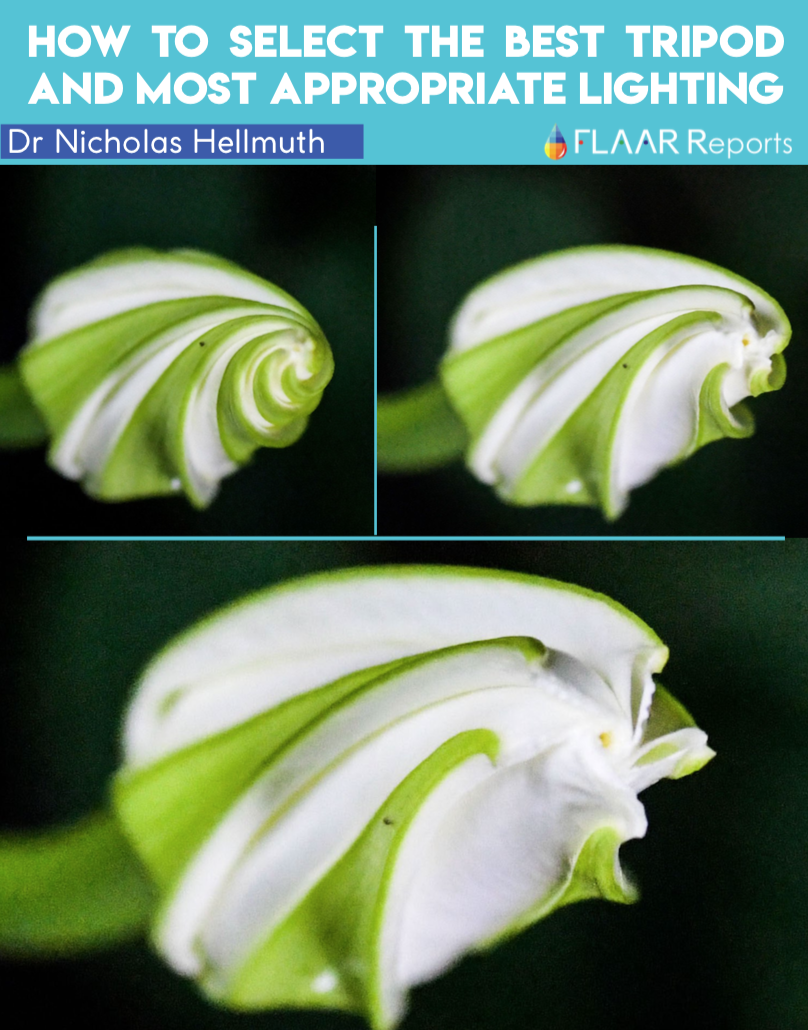

Foods of the ancient Maya included two edible bromeliads called piñuela

Cyrus Lundell’s 1937 monograph lists both bromeliad species as edible: Bromelia karatas and Bromelia pinguin (page 54). He mentions B. karatas five times and B. penguin once. In his 1938 article, Lundell lists only Bromelia karatas L. Cham.

Bromelia karatas is my absolute favorite terrestrial bromeliad to photograph

|

|

I had never noticed this edible plant until Senaida Ba showed it to me, growing wild in the hillside surrounding her Q’eqchi’ Mayan family home (Chipemech, Senahu, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). |

|

In late 2018 we found Bromelia karatas growing on the east side of the road to the Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo, near the signs that tell you the entrance is about 6 km further on. But the teams who are under orders to clean away all vegetation from both sides of the road destroyed this bromeliad before we could study it further. It would be helpful if useful and edible plants that grow along the roads could be saved from being chopped down (especially since this bromeliad was in front of the fence line, so over 2 meters from the edge of the road). |

Bromelia pinguin is also a Mayan medicinal plant

|

|

Bromelia pinguin in its standard location on the ground.. You can find Bromelia pinguin used as a living fence around Monterrico (on the Pacific Ocean coast of Guatemala). You see more living fences of Bromelia pinguin along the road through the dry areas of Jocoton, en rote to Copan Ruinas (across the border into Honduras). And you can find Bromelia pinguin growing in the dry Motagua River desert area parallel to Highway CA9 (Guatemala to Puerto Barrios). But to see the Bromelia pinguin there you have to leave the main highway and drive down into the valley (to the north of the highway). From km. 60 to km 80 there is a log of in that dry area parallel to the main highway.

Because is so common in dry areas, I am still curious of whether we are going to find lots of growing throughout the Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo. We have found lots of non-flowering terrestrial bromeliad plants between Yaxha and Nakum, and in other dry bajo areas of the park. But until they flower we do not know what species they area. In the same identical area between Yaxha and Nakum we have found two pital areas (Poza Pucte and Poza Sardina) where Aechmea magdalenae grows in a ring around seasonally dry aguadas. We found another identical eco-system near El Tigre (on the western border of PNYNN). There are comparable pital areas throughout central Peten and elsewhere in the Mayan areas. Aechmea magdalenae is always in extensive thorny thickets, and always terrestrial. Aechmea magdalenae produces a highly prized pita or thread, one of the best materials for weaving selected materials. Aechmea magdalenae is an obvious distant relative of the pineapple. The pineapple is not native to the Mayan nor Aztec areas despite many books on plants before Columbus. There are no direct ancestors of the pineapple in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, or Honduras. Aechmea magdalenae is a distant relative, not an origin from which the pineapple descended. |

There are scores of books and articles on medicinal plants of the Maya. Bromelia pinguin is one of the plants mentioned (especially for Yucatan, as ch’om in Yucatec Maya; sometimes spelled ch’am or even ch’um). I would estimate that Bromelia karatas is also potentially medicinal.

Most bromeliads grow high up in trees

But we are studying all the Bromeliads which live on the ground

Aechmea bracteata is common in Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo because it can grow “anywhere:” on the ground or high in trees; in dry areas or in wetter areas. When you see it on the ground often it is because, due to its weight, it has fallen to the ground when the branch on which it was sitting has broken.

Once the branch rots, the Aechmea bracteata continues to grow.

You also see the Aechmea bracteata bromeliads growing in the fork in a tree. So this plant is very adaptive.

Bromelia karatas and Bromelia pinguin both grow on the ground (as does the pineapple). Both are extremely thorny, which is why Bromelia pinguin is used as a cerco vivo (living fence). But the plants named piñuela are bromeliads, not henequen, margay, or agave.

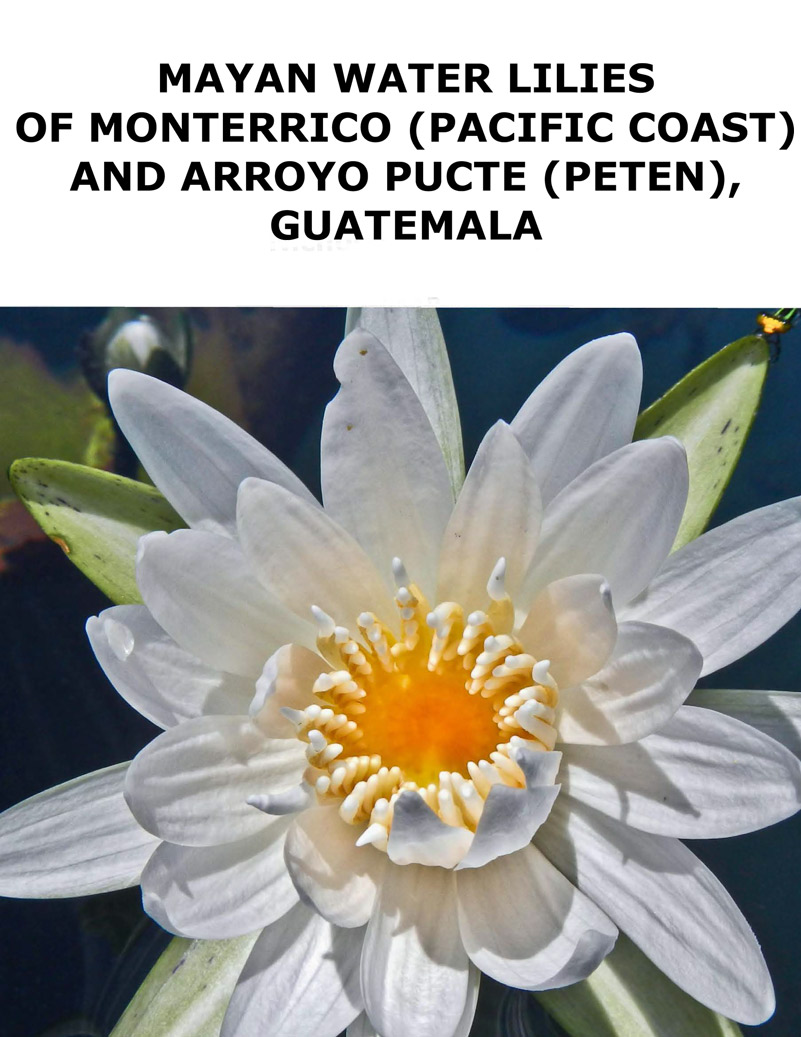

Bromelia pinguin prefers dryer areas; Bromelia karatas prefers areas with more rain (such as the Chipemech area of Senahu, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Bromelia pinguin can grow in the salty sand facing the Pacific Ocean (as a living fence for CECON Tortugario, Monterrico).

Androlepis skinneri is an epiphyte but also is content on the ground

|

| Every month we have found an Androlepis skinneri bromeliad in full bloom in different areas of Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo. The flowers last about two months but then we find a different plant several kilometers away that is in full bloom the next month. Although Androlepis skinneri is classified as a epiphyte, normally we find it on the ground or on a fallen tree branch. But sometimes it is totally on the ground and completely happy (same as with the Aechmea bracteata; these can be arboreal high in the tree tops, or fallen and still on top of the fallen trunk or fallen branch. Or, if the plant is blown off the tree it can still grow happily on its own on the ground. Photograph using a Google Pixel 3 XL telephone camera by Juan Pablo Fumagalli, FLAAR Mesoamerica, January 21, 2019, along the road between Yaxha and Nakum, |

We have a separate bibliography on piñuela of the Maya

One article we include in the bibliography makes a surprising claim:

The only other C4 plants possibly available to the Maya which might confound the maize signature would be amaranth (amaranth sspp.), epazote (Chenopodium ambrosoides) and the CAM plants; nopal cactus (Opuntia) and pinuela (Bromelia karatas) (Wright & White 1996). None of these, however, are expected to have been consumed in any significant quantity by the Maya (Powis et al. 1999: 371).

Yet amaranth is widespread throughout the Highlands of Guatemala (and I would estimate also in Mexico). Although everyone calls it “the Aztec equivalent of quinoa of the Inca” in fact amaranth was and still is consumed by the Maya of Guatemala.

Guatemalan botanist Dr Cezar Azurdia is quite knowledgeable in the many species of this plant, both wild and cultivated.

Epazote is in many people’s list of “underutilized plants of the Maya.” Nopal cactus grows in many areas of Guatemala though I will admit that in six years it has bloomed only once in our ethnobotanical garden at 1500 meters elevation. But Nopal cactus is readily available to eat if you are at lower elevations.

Last but not least, there are TWO edible species of piñuela, and the family of our Q’eqchi’ Mayan student intern (from the remote area between Senahu and Cahabon) eat Bromelia karatas. What I am learning is that during the 1930’s through 1990’s, the old traditional concepts of Mayan foods was still fixated. Most of these authors did not hike through the mountains between Senahu and Cahabon; these botanists did not visit the Q’eqchi’ Mayan markets of Senahu and other remote villages.

There are also other bromeliads of use in Mayan areas:

There is a lot to learn about Maya use of bromeliads. Among others, I suggest looking at:

• Bromelia alsodes St. John [syn. B. slyvestris Burm.f.]

• Bromelia hemisphaerica Lam.

(Kermath, Bennett and Pulsipher 2014: 142-143).

Our project of finding all edible and all useable plants available to the Classic Maya several thousand years ago is still in its first months. But we are learning about new plants every week that we are able to get to the park (a one thousand kilometer round trip drive each month, every month).

|

Most recently updated June 2019

First posted July 27, 2017