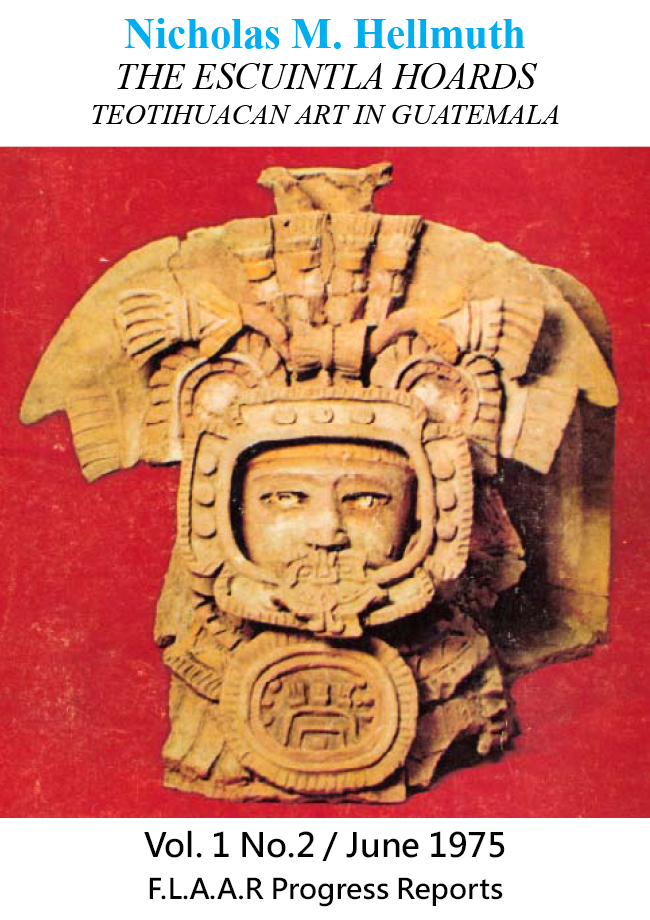

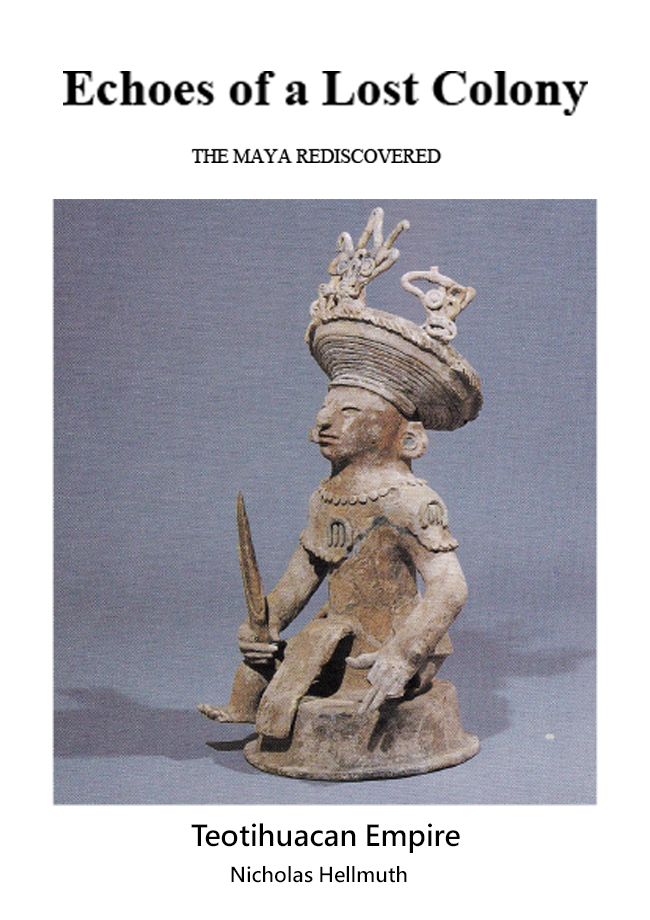

The architects of 3 rd -6 th century Guatemala made full-scale 3-dimensional models in fired clay of some of their wooden temples. These models are about 15 to 25 cm high. They are complete with roof, sometimes even a roof-comb decoration. Most of these scale-model temples even have seats inside and seated personages, as well as attendants standing outside. I have seen perhaps five to seven such temples over the past 30 years in exhibits, but it was not until this year (2009) that I had the time to photograph one completely.

I thank the curator, Susana Campins for permission, as well as the curator of the museum (literally next door), Ana Claudia Monzon, for faciliting the several days of photography in the two museums. Both these museums are inside the Hotel Casa Santo Domingo. Each of the museums is physically and administratively separate, but they are about 4 meters from each other (in adjacent rooms actually).

I had visited the Museum of Pre-Columbian Art and Modern Glass about a week before and had noticed the architectural model, but I did not notice any of the fine details until I set up a complete photographic studio with full-scale studio lighting. Frankly I was bowed over by the detail that the lighting revealed. This is, in size, one of the smallest of the architectural temple models I have seen, but after the first 10 minutes of having it properly illuminated, I quickly noticed that iconographically, it is probably one of the five most important ones in the world. So it is very nice that such an excellent example of Early Classic Teotihuacan-related Tiquisate Escuintla art is available for study still in Guatemala and in a professional museum environment.

|

|

Here is Dr. Nicholas Hellmuth photographing an Early Classic Teotihuacan-style temple effigy from the Escuintla region. Here we are using special digital lighting which is cool (so not tungsten halogen), along with a 22-megapixel digital camera, Zeiss lenses for good quality. (Paseo de los Museos, Hotel Casa Santo Domingo. Antigua, Guatemala 2009).

|

|

|

Three-quarter view of the back of a Teotihuacan-style temple effigy. Coleccion Museo VIGUA de Arte Precolombino y Vidrio Moderno, Paseo de los Museos, Hotel Casa Santo Domingo. Antigua, Guatemala 2009. FLAAR is preparing an article on this genre, at which point the front and all sides will be shown, in full detail, in full color.

|

Museum of Pre-Columbian Art and Modern Glass, Hotel Casa Santo Domingo

Edgar Castillo Sinibaldi has devoted years of knowledge of pre-Columbian Guatemala to create a lovely collection. This collection is strong in material from the Costa Sur area of Guatemala. The Costa Sur in this case means the Departamento of Escuintla area plus east and west through neighboring departments. This is the extensive area of significant Teotihuacan impact as well as an area of several concentrations of earlier Olmec influence.

Although I have been aware of the collection of Edgar Castillo though his courteous invitations to view it in his house in past years, I never did systematic photography of more than a few samples. When I visited his Museo de Arte Precolombino y Vidrio Moderno in summer 2009, I noticed more pre-Columbian works of art than I had remembered (though all have been in his collection for many years).

Through the courtesy of the museum staff including curator Susana Campins, it was possible to spend a day and a half in August 2009 photographing selected items. I had intended to photograph about 12 artifacts, but found that the first six were so exceptional that I spent hour after hour after hour on them alone.

This web page is not intended to be a full divulgation of even one of these (since a web page is not large enough to give the full iconography, and resolution of the Internet does not do this piece justice). Plus I wish to undertake 3D scanning of the entire temple model so that we can prepare 3D architectural drawings, as well as elevations and renderings. Such drawings would be for a future article in an appropriate journal or magazine.

Postscript

I am writing this web page en route to lecturing in Johannesburg, South Africa. I do not have a library with me, and in any event I doubt if most libraries in Central America have the key exhibit catalogs that have the other temple-themed incense burner lids from the rest of the Escuintla Hoards of the Costa Sur of Guatemala.

But I did find one architectural incense burner lid pictured nicely on the Internet, though of course the image was so small as not to be usable for detailed iconographic analysis.

Another pre-Columbian architectural model of a Tiquisate style temple as an incensario lid: Boston Museum of Fine Arts

The Landon Clay collection donated to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts includes a nice example of an architectural effigy. It has a complete roof, roof comb and lower platform. It was the custom for whoever was digging up these incensario lids to save up extra adornos and glue them on when they needed to add decoration, so it would require a detailed laboratory analysis of the clay of each adorno to ascertain if they all really belonged. For example, the adornos stuck onto the pillars and lintel are not very convincing (but I would need to see the original to know for sure). These adornments appear original in themselves (it is the position that I doubt is original), but I would need to check to be sure. The roof should also be checked to see what portions are original and what are restoration, but the style is correct either way. The presence of standing human figures is also correct, though their position should be checked. Normally they should be standing next to the front columns.

Following is the tag for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts comments on their attractive example of another temple model as an incensario lid from the greater Escuintla area.

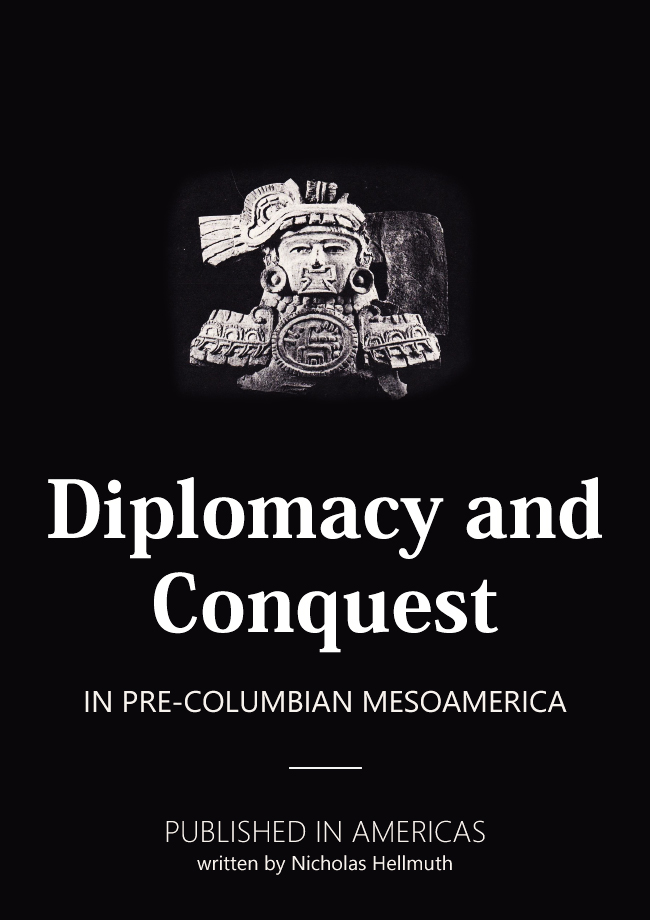

Effigy Incense Burner Top

Maya, Early Classic Period, A.D. 400–550

Guatemala, Southern Highlands, Tiquisate Region?43.5 x 43.3 x 28 Cm (17 1/8 x 17 1/16 x 11 inches)?fired earthenware with traces of red and yellow post-fired paint?

Teotihuacán-Style Effigy Incense Burner With Figure Rendered Inside A Temple Surmounted By A Geometric Roof Comb. Butterflies, Stars, Floral Motifs, And Feathered Disks (Mirrors?) Decorate The Building. This Type Of Incense Burner Is Typical Of The Tiquisate Region In Southern Guatemala, Made In Imitation Of The Characteristic Incense Burners Of Teotihuacán In Highland Mexico.

I would suggest rewriting this:

First of all, there is nothing Maya about this incensario: neither the style, content, nor Department of Escuintla is “Maya” in any way shape or form. Otherwise, the Early Classic date is within reason.

Second, this is not the Highlands whatsoever (Teotihuacan itself was in the Highlands several thousand kilometers north in Mexico, but Escuintla is coastal to piedmont: Escuintla is not really part of the Guatemalan Highlands). At most it is the piedmont, but Costa Sur is a better description. Tiquisate region is acceptable, keeping in mind that Teotihuacan inspired but locally made objects occur all the way west to close to Retalhuleu

Finally, although incensarios in Escuintla are indeed made in memory of incense burners of Teotihuacan, there are rarely any architectural incense burner lids at eotihuacan or elsewhere in Mexico. This concept, of a temple as an incensaro lid, is featured primarily in Guatemala, not in Mexico. So this specific concept (a 3-dimensional temple) is not really an imitation of a common style of incensario lid in Highland Mexico.

The list of motifs is more or less acceptable in general terms. A full iconographic analysis would suggest more details, but the present Boston description is a good start.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts nicely provides relatively good-sized professional quality photographs of its ceramics for study on their museum web site.

Third example: private registered collection, Guatemala

A third example of a Tiquisate temple effigy as the main decoration on an incensario lid is in a registered private collection in Guatemala. Since I do not have photographs of this yet, I do not yet illustrate it.

The temple corners are clear; the tablero of the front terrace is cear and the same shape as that of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts example, but the stairway balustrades are not preserved fully on both sides. The interior appears to have one seated personage not two (but I would have to inspect the incensario in person). There is one personage standing in front of each column, but more dwarflike than natural sized, especially compared with the seated figure inside.

Although badly preserved and not restored the pieces and positions appear to be generally authentic. It is an asset that it is not restored. Most restorations introduce forged parts or at least forged positions for the adornos

Other examples of temple effigies in 3-dimensions as lids of Tiquisate-Escuintla incensarios

I estimate there are between three to five larger, more complex, and better preserved temple incensario lids in collections outside Guatemala and probably two to four smaller temple-style incensario lids still in Guatemala collections. It is hoped that Tiquisate lids can remain in Guatemala so they can more easily be studied.

Tablero-Talud incensarios from Lake Amatitlan

The purpose of this page is to introduce this newly recognized architectural model to archaeologists and architects. A full study of the genre will take a year or more, and should include comparative comments on incensarios from Lake Amatitlan. Unfortunately the article by Dr Mata does not include any illustrations.

MATA Amado, Guillermo and Rolando Roberto RUBIO

1994 Incensarios talud-tablero del lago de Amatitlán, Guatemala. En I Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1987 (editado por J.P. Laporte, H. Escobedo y S. Villagrán), pp.27-37. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala .

FLAAR is inherently interested in all architectural aspects of pre-Columbian civilizations

The background of FLAAR includes the Early Classic and Late Classic architecture of the Maya of all regions: Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras. I have been studying these temple, pyramid, palace, and ballcourt remains since I was 16 years old. My high school thesis on the ruins of Bonampak won first prize at my prep school (and helped get me accepted at Harvard). Indeed the following summer, at age 17, I was accepted by an INAH team to go to Bonampak as an observor for their project. I majored in architectural sciences for the first three years at Harvard, switching to anthropology/archaeology after I did archaeological studies of Mayan architecture at Tikal for the University of Pennsylvania Tikal Project in 1965.

In the 1970's through 1980's, FLAAR photographed extensively in the Puuc, Chenes, and Rio Bec areas of Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo. The FLAAR Photo Archive of Mayan architecture is probably larger than that of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. The images are crisper and taken with better lighting and more professional camera equipment than the extensive and important photographic archive of architect George Andrews and capable Mexican architectural historian Paul Gendrop.

FLAAR used primarily medium format Hasselblad camera equipment, and for 35mm, Leica and Nikon. For lighting in some years we brought an entire set of five of the largest German flash units that we could find: Metz. This is because many of the ruins are under dense tree cover. With five flash units we could illuminate a large section of façade (of course this was time consuming and we could not do it every day).

Eldon Leiter and Jack Sulak also have nice photographic archives of Puuc, Chenes, and Rio Bec architecture of the Classic Maya.

So we are instinctively interested in Mayan architecture, as well as the architecture of Teotihuacan, Tula, Aztecs, Zapotecs, and Mitla.

|

Copyright notice Both FLAAR and the museum tend to be generous for scholarly use of these images, but dumping images on a web site that does not provide significant scholarly commentary or meaningful original discussion is not what most people envision as scholarly use. It is preferred that the images be used for scholarly articles in appropriate journals and magazines, or for a thesis, dissertation or monograph. We also encourage usage to assist visitors to Guatemala to learn about the pre-Columbian cultures of Guatemala, but in a professional manner (which means more than just dumped in a batch of continuous photographs with not much original discussion). Stealing an image is not “fair use,” especially when the original photographer and original web site are not clearly, specifically, and appropriately cited. Fair use is quoting small portions of text; reproducing entire images is cheating. These images are more than copyright; permission to use them understandably requires permission of the Museum, and of the FLAAR Photo Archive. |

First posted September 8, 2009.