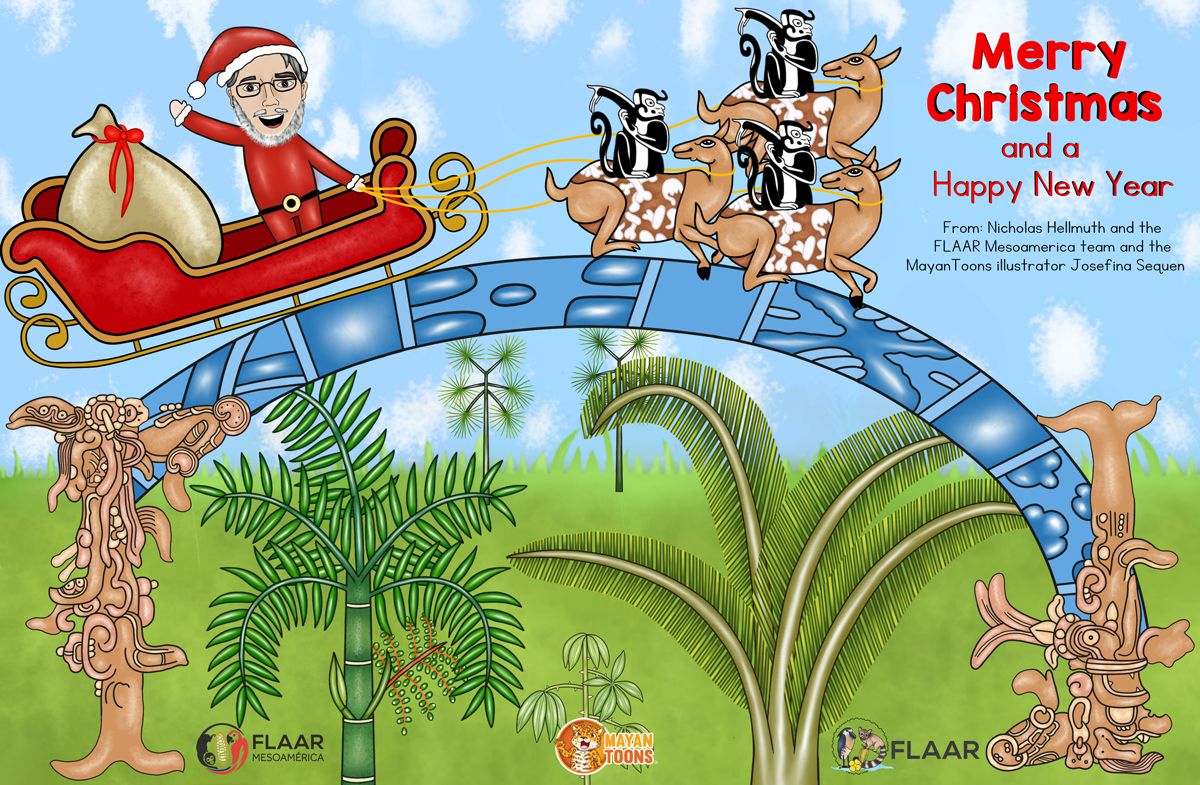

Merry Christmas 2025 and

Happy New Year 2026

Posted December 24, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

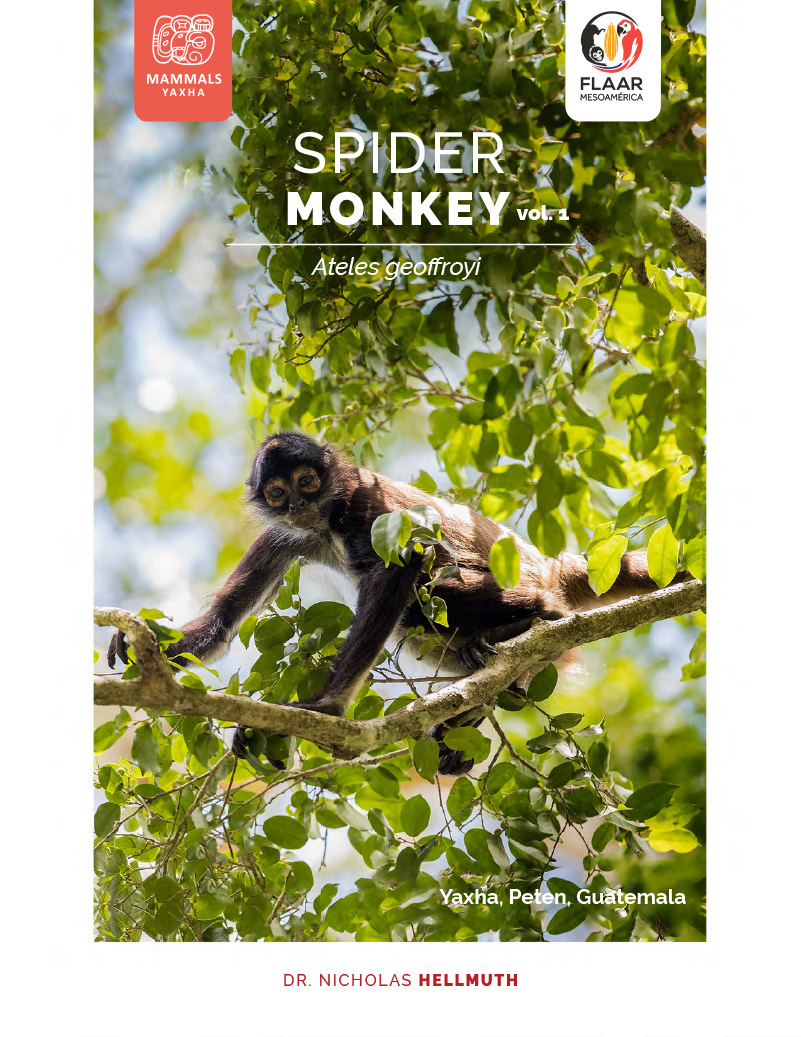

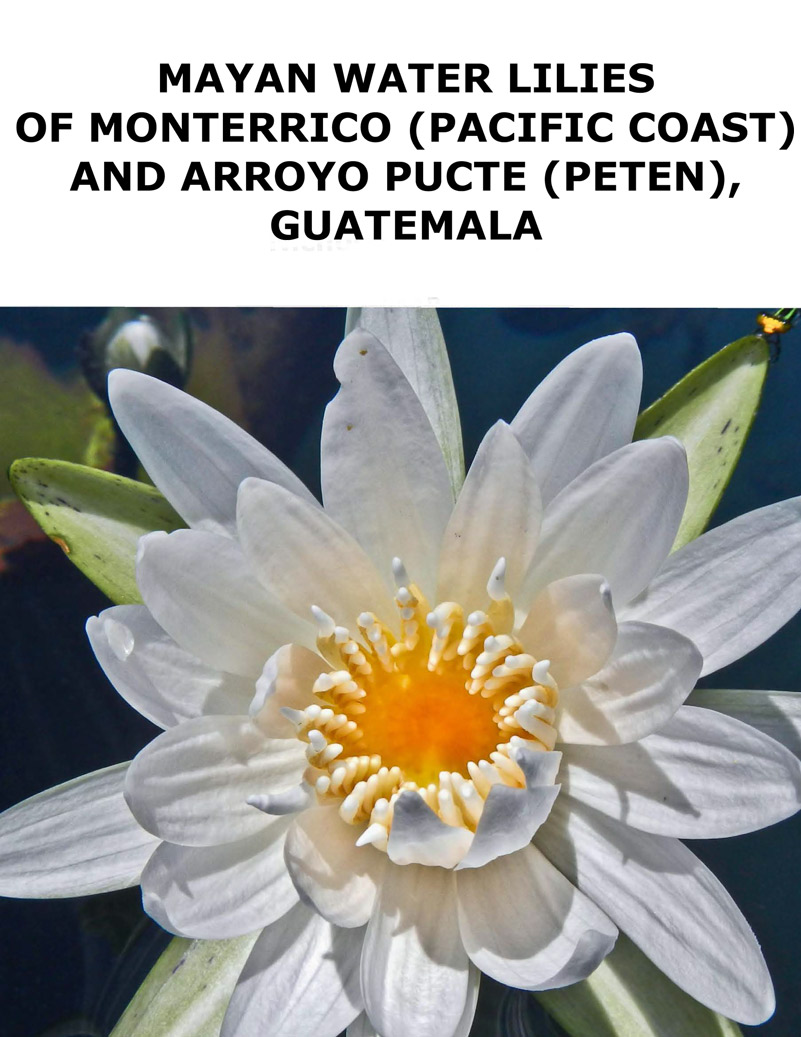

This is "Santa Nicholas" being pulled by native deer of Guatemala. The same species of deer that are common throughout the USA are also native and wild even in the rain forests of Guatemala. In Classic Maya art deer are often associated with monkeys—some Maya portraits of deer feature an obvious monkey tail on the deer. And paintings of monkeys often show them with deer antlers and deer ears.

The circular path is the Maya Sky Band with celestial motifs. We have published many PDFs on this topic. Just Google Sky Band Hellmuth FLAAR.

Often the Sky Band is the body of a Bicephalic Cosmic Monster, with "starry-eyed" deer at the left and an upside-down Quadripartite Badge Headdress monster at the right. Just Google Bicephalic Cosmic Monster, crocodile lecture, Hellmuth and you will see lots of Maya art with this cosmic monster.

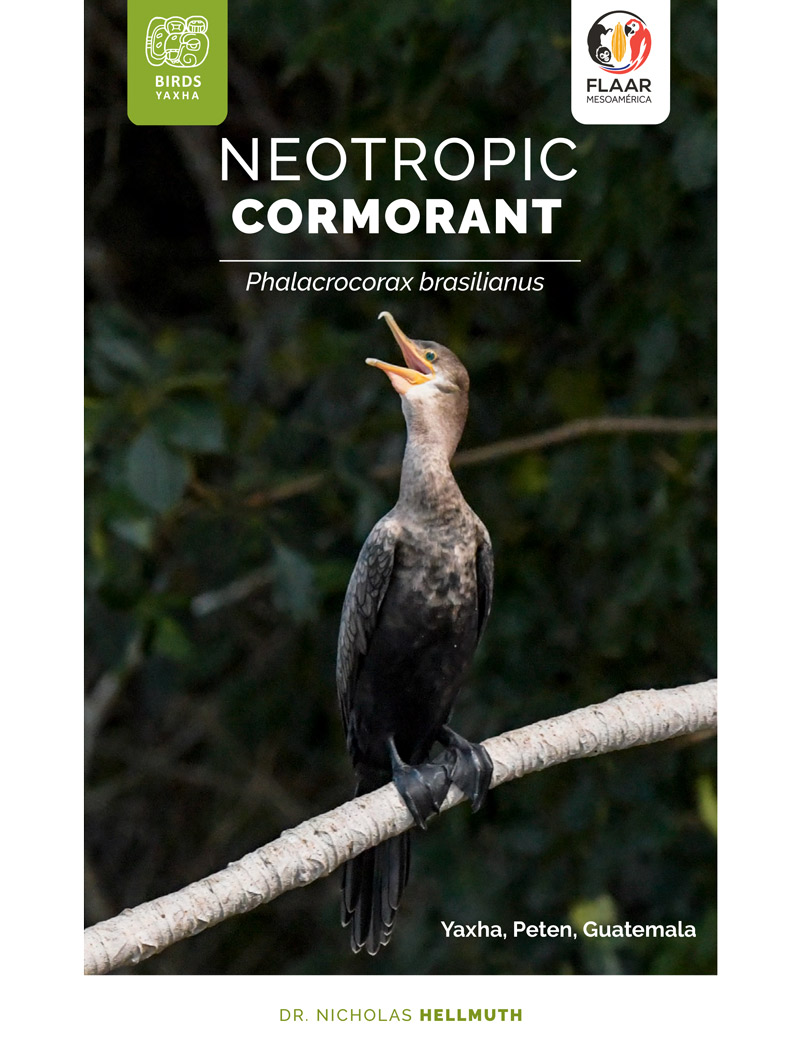

For year 2026 we will continue with new iconography reports on deer, on monkeys, on bats, on rabbits, on macaws and fish and other native fauna featured in Maya art at the national museum of art and ethnology of Guatemala. The goal is to prepare educational material for the literally hundreds of school groups that visit the museum every month plus the thousands of tourists who also visit this prestigious national museum.

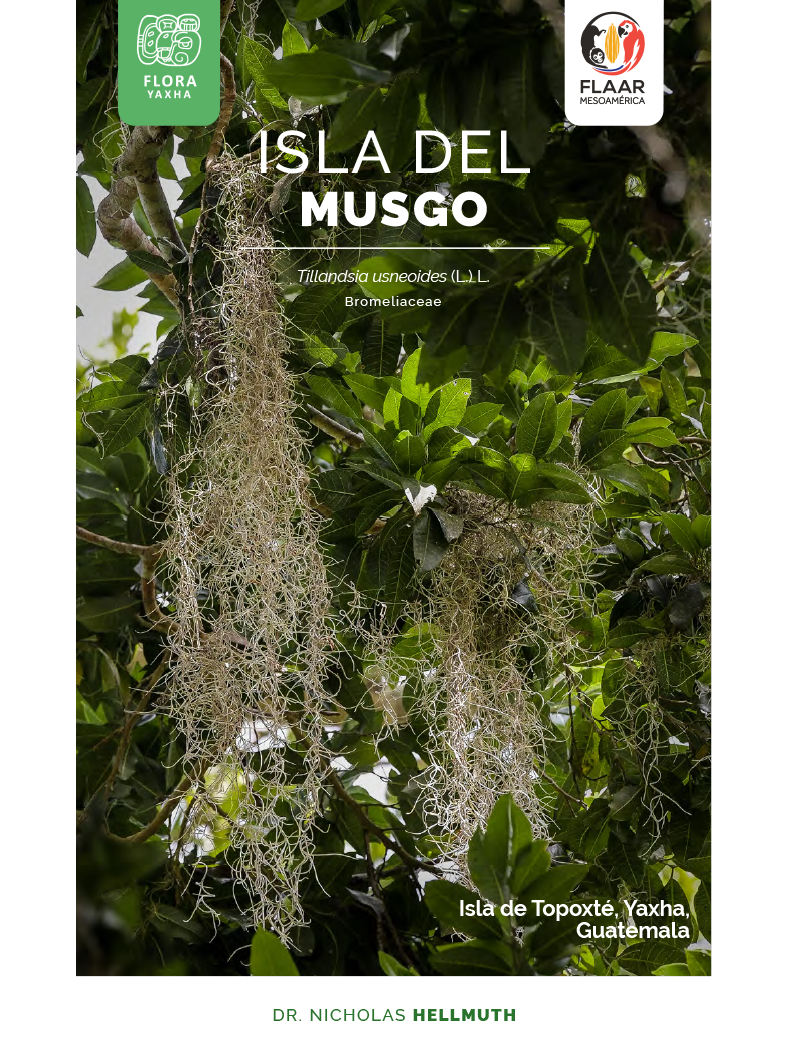

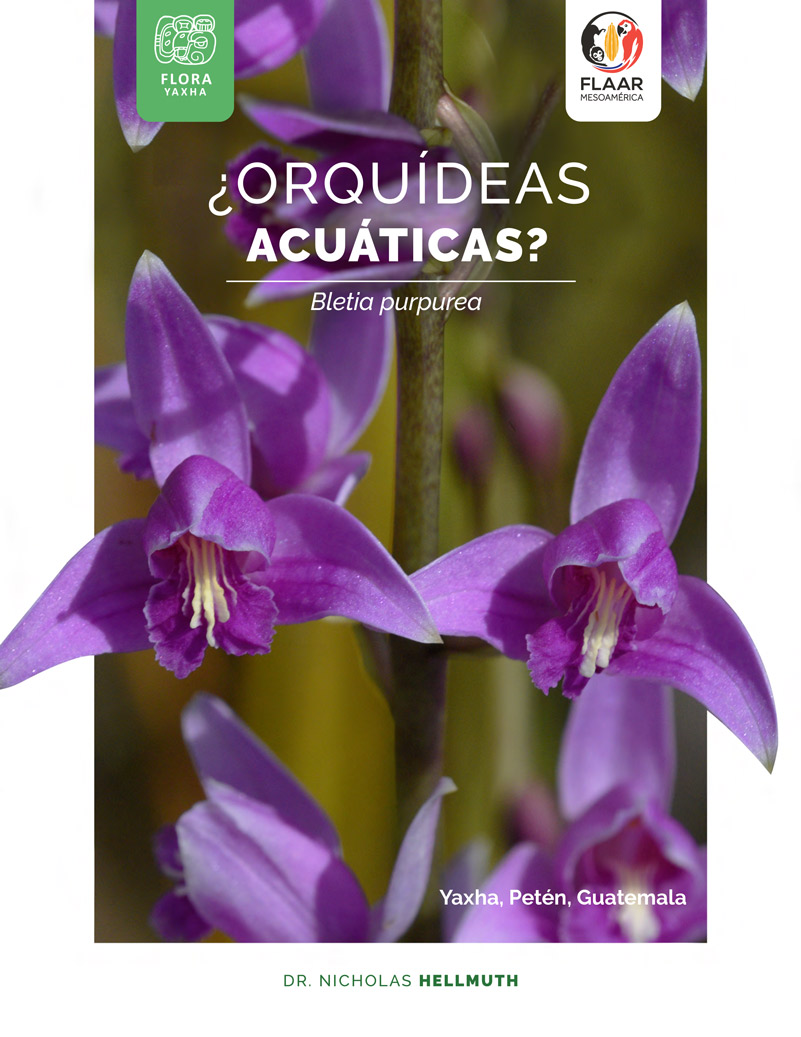

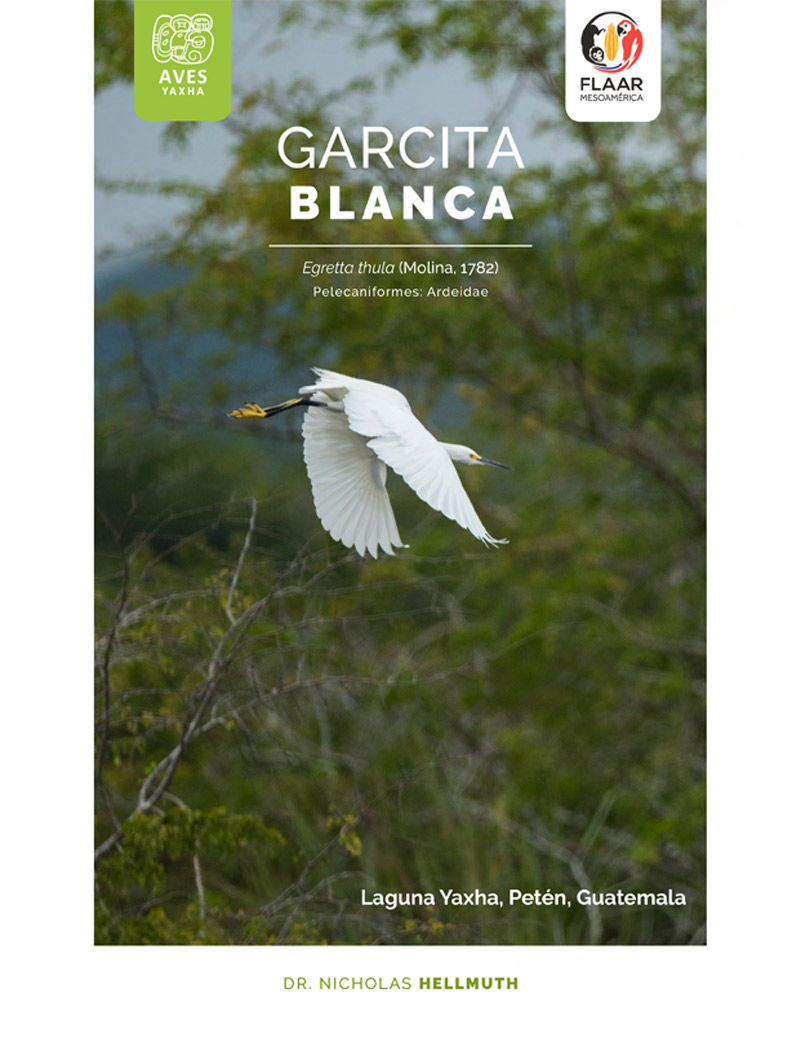

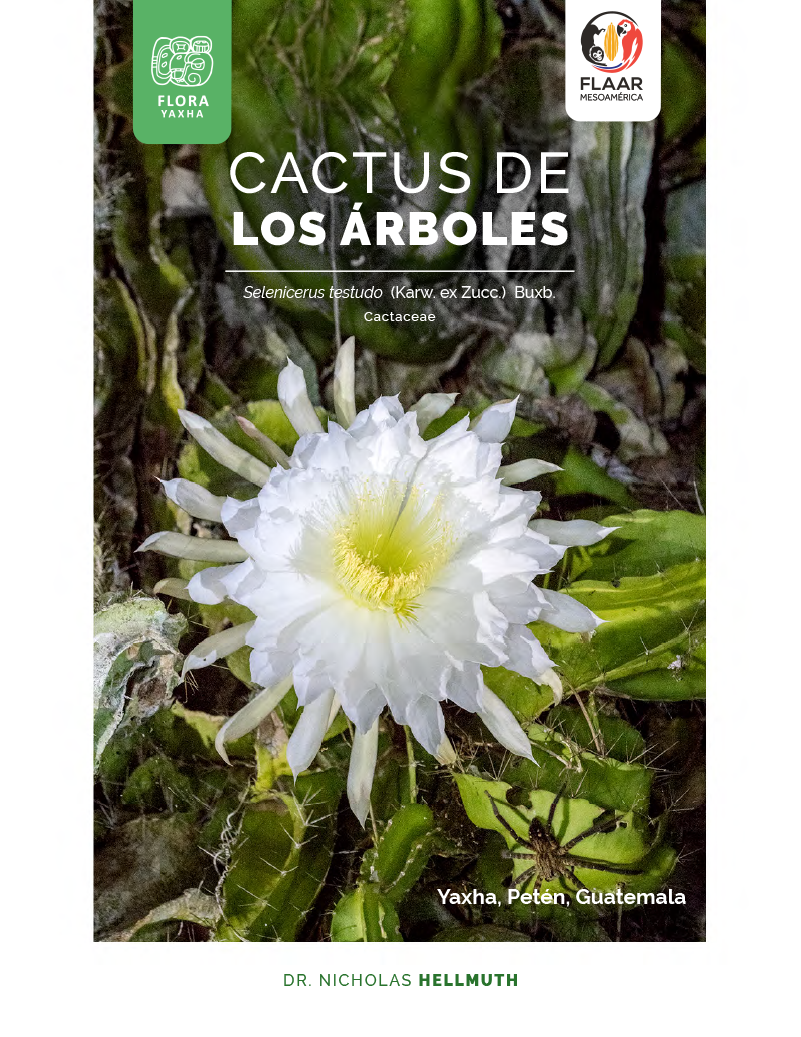

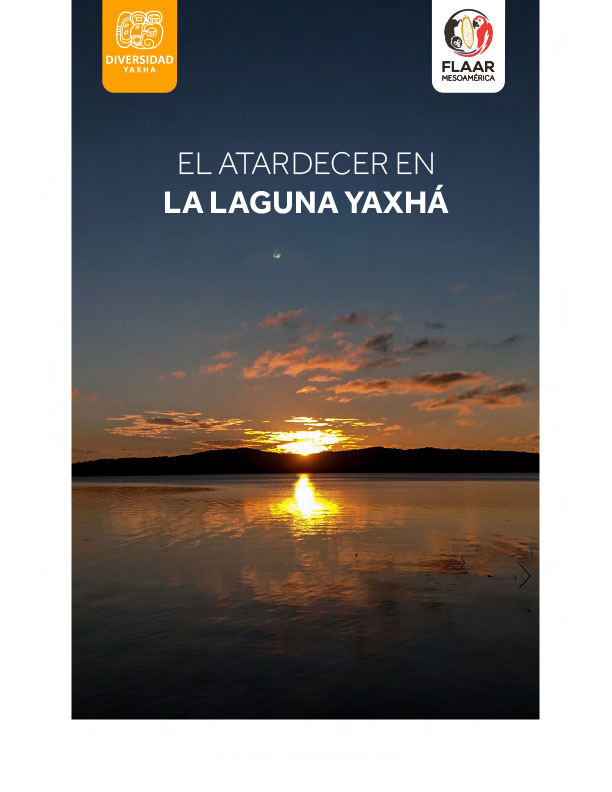

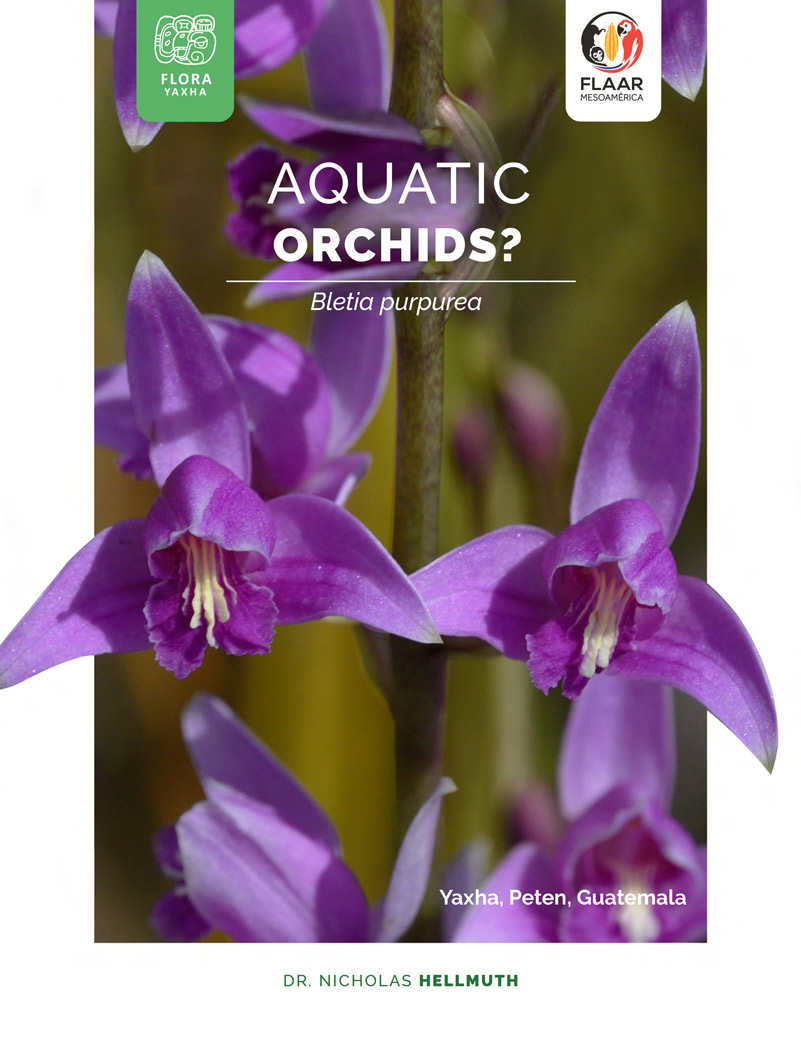

Simultaneously we will be engaged in field trips and library research on flora, fauna and biodiverse ecosystems of the Reserva de la Biosfera Maya, RBM, Peten, especially of Parque Nacional Yaxha, Nakum and Naranjo (PNYNN) and surroundings.

We now have a new Mavic 4 Pro drone whose aerial camera is significantly better than all previous models that we had in recent years. Most importantly for working in national parks, the Mavic 4 Pro can be flown at eye-level through the forest—so we can show eye-level views in addition to the obviously important aerial views from above.

We also continue our long-range research project on all the hundreds of wild plants, native to Guatemala, have edible parts. With the help of the Q’eqchi’ Maya team that work with us, we are preparing FLAAR Reports on several wild plants of the cloud forests of Alta Verapaz that produce edible food without needing slash-and-burn milpa agriculture.

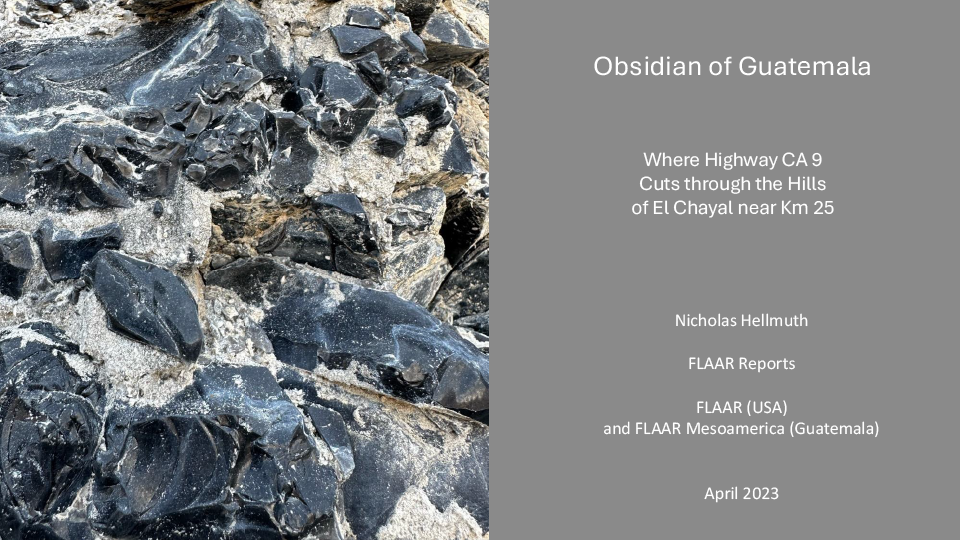

Obsidian was available to the Classic Maya in Black, Gray, and Mahogany Colors

Posted Octuber 27, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

The Classic Maya of Guatemala did not have metal for tools or weapons, so the ancient Maya mined and worked obsidian to make tools, weapons, and jewelry. Obsidian carved in the shape of the moon and planets and constellations were placed under stelae in Peten and surrounding areas. Chert (also called flint) eccentrics were also used in stelae caches.

The Classic Maya also imported green obsidian via Teotihuacan trade routes, but that obsidian from Pachuca area of Mexico is very rare at Maya sites of Guatemala.

Obsidian is “volcanic glass” and thus found in many volcanic areas of Guatemala. The obsidian source closest to Guatemala City and easily accessible by highway CA 9 is El Chayal.

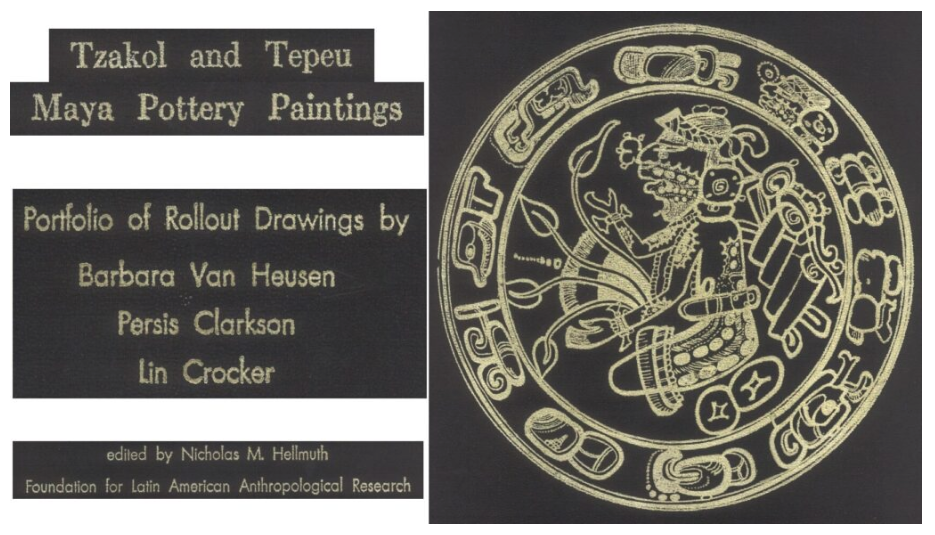

Drawings of Late Classic Maya Plates and Rollout Drawings of Maya Vases

Posted August 29, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

In 1976 about fifty rollout line drawings of Maya vases and several drawings of Maya plates were issued as a printed portfolio. I estimate that only between 50 and 100 were printed. These are in libraries at major universities around the world.

But in today’s digital world, you don’t have to waste time going to a library to search for a book—you can download the book, article, thesis or dissertation on-line.

So our goal at FLAAR is to make available all the 1960’s, 1970’s, 1980’s, 1990’s publications in PDF format and available at no cost—plus you do not have to register—just download.

The original portfolio had about 56 drawings at double-page width—so the drawings could be at a healthy horizontal rollout format. Since the original edition was loose individual sheets in a portfolio envelope, most libraries lost several pages over decades. We also are missing Figures 6, 7, 15, 39, 45, 46, 47 and 49. We would greatly appreciate it if your university or museum library has these pages in the original portfolio so you can kindly send us a nice scan of as many of the missing pages that you can find. We would like to issue a year 2025 update with more documentation for each scene—but need to have all the missing images.

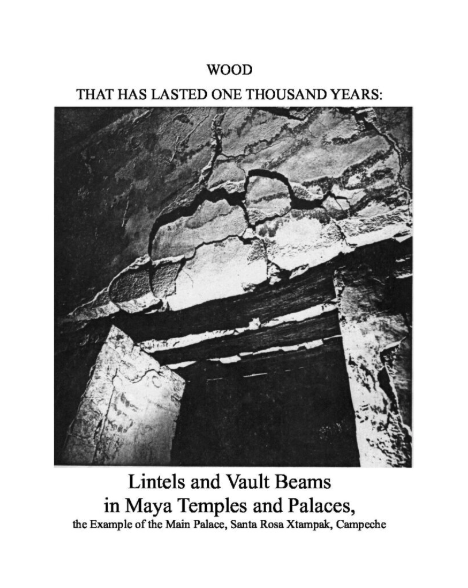

FLAAR publications on monumental Maya architecture All three regional styles (Puuc, Chenes and Rio Bec) at one site: Santa Rosa Xtampak, Campeche, Mexico

Posted August 29, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

Maya temples, palaces, acropolises and ballcourts were my research focus starting in 1961, when, at age 16, I went from my Spanish language school in Saltillo, Mexico (north of Monterrey) all the way to Palenque, Chiapas, in 3rd class buses. I stayed several days at Palenque, using a Leica camera that my father had loaned me. I took photos of the Classic Maya architecture but also the rain forest surrounding the ruins. I went back to Saltillo and then drove back to St Louis where I did my high school theses on Maya architecture. Since not many high school students write their thesis on Classic Maya architecture, my thesis won 1st prize in my class. This helped me get accepted to study architectural sciences at Harvard because I was not at the top of my class—universities also want people who do atypical projects. Then a year or so later I was kindly accepted by an INAH team what I met in Tabasco to help them carry their equipment and baggage the many kilometers to Bonampak, and I also offered to help them set up their camp. No airstrip at Bonampak in the early 1960’s, so your Cessna landed at a Lacandon village far away.

Then the Tikal Project asked me to help them as an architectural recorder and photographer at Tikal for an entire year of 1965, so again, my focus was on Maya architecture an entire year. During the 1960’s I also visited lots of Puuc ruins and in the 1970’s and 1980’s lots of Chenes and Rio Bec ruins. So when I learned that Santa Rosa Xtampak had a palace with a Chenes monster mask and also Rio Bec towers I coordinated with William Folan and the INAH team in Campeche to have a permit to accomplish photographic documentation of Santa Rosa Xtampak. While there in 1989 we noticed and documented Puuc architectural features in addition to the Chenes and Rio Bec aspects.

We have dedicated lots of time and effort to scan all our 1989 reports and wish to make them all available to INAH of Mexico and to archaeologists and students around the world.

We have been unable to find the helpful publication of Eldon Leiter, 1989, Inventory of the Lintels of the Main Palace at Santa Rosa Xtampak. If anyone in Campeche has a copy, a PDF would be appreciated.

Lots of capable 3D digital documentation of the main palace are by Erwin Heine, also from Graz. All his work cites his team; all their publications are in the bibliography of the remarkable 3D reconstruction of the main palace by architect and architectural historian Hasso Hohmann, also from Graz. FLAAR was headquartered in Graz before, during, and after Hellmuth’s 1986 PhD dissertation, but also simultaneously in 1989 as a guest visiting research professor at Rollins College, Florida. Hellmuth was also simultaneously a Guest Visiting Research Fellow at Yale University for multiple appointments, including 1989.

- 2017

- The Maya Temple-Palace of Santa Rosa Xtampak, Mexico. Documentation and Reconstruction of Form, Construction, and Function. Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz. Austria.

Super-helpful that this university put the entire book on-line as a nice download:

https://diglib.tugraz.at/download.php?id=5def5202c2bd7&location=browse

Trees, Beverages, and Maya Cacao Glyphs

Posted August 25, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

We warmly invite you to join us for the Universidad Francisco Marroquin, lecture: Trees, Beverages, and Maya Cacao Glyphs, where we will explore the fascinating world of cacao in ancient Maya culture. Discover the symbolic role of trees, the importance of cacao-based beverages, and the rich legacy preserved in Maya glyphs. This event offers a unique opportunity to connect history, culture, and tradition, while deepening our appreciation of one of the most cherished plants of Mesoamerica.

Thursday, Aug. 28, 2025, 7pm, Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquin, lecture Maya Cacao Trees, Maya Cacao Drinks, Maya Cacao Hieroglyphs, And Cacao Pods shown in Classic Maya Art and Tiquisate Style Ceramic Female Portraits Revelation of LOTS of other Native Fruits of Guatemala are same Size and Shape as Cacao Pods.

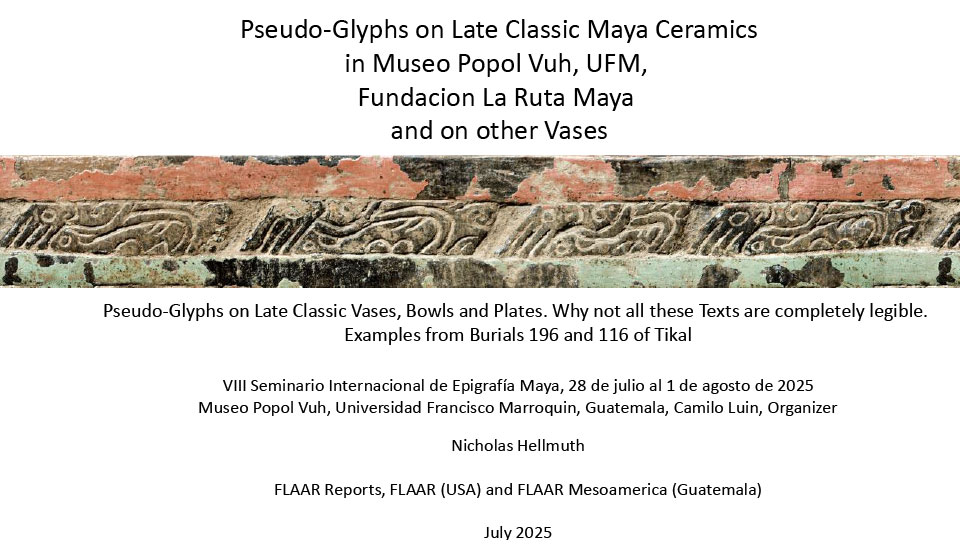

Previously unpublished Late Classic Maya Pseudo-Glyphs now available to study

Posted August 14, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

Inga Calvin has dedicated considerable research and an excellent year 2006 PhD dissertation on Maya pseudo-glyphs. But today in 2025 there are dozens and dozens of additional (previously unpublished) Maya vases, bowls, and plates with pseudo-glyphs, so it is helpful to make all these texts available to epigraphers, linguists, iconographers, and ceramicists. There is now material for a completely new PhD dissertation that can learn from the suggestions in the July 31st epigraphy presentation by Nicholas Hellmuth.

This PDF is the English version of his Spanish presentation (the updated Spanish edition will hopefully be available next week). The present 196-page English edition has over a dozen new photos to add to the extensive corpus in the lecture. We coincide with multiple epigraphers who agree that some of these “pseudo-glyphs” should be studied in depth to learn which types of pseudo-glyphs are actually written to present a message.

VIII Seminario Internacional de Epigrafía Maya, Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquin, Guatemala, Camilo Luin, Organizer.

Full-Figure Personified Maya Hieroglyphs now available in a Thousand-Page MA thesis

Posted July 1, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

Since I have been studying full-figure Maya hieroglyphs for several years, I was pleasantly surprised to find a 1,064 page opus that is the most comprehensive list (inventory, catalog) of full-figure Maya hieroglyphs ever published.

He shows more full-figure Maya hieroglyphs than Morley, Thompson and all other books “Introductions to Maya Hieroglyphs” combined. I have been preparing lists of full-figure Maya glyphs since 2023 and I estimate that Mauricio Moreno Magariño has found and documented many more that I had not yet found.

If you are an epigrapher, iconographer or archaeologist this thousand-pages of hieroglyphic research is essential. It is the most comprehensive corpus of full-figure glyphs ever amassed—with the majority cited as to source (site and sculpture name), illustrator, and where published.

If you are a student or member of the interested public, and you would like to learn more about Maya hieroglyphs, full-figure glyphs are the easiest way to learn—since each glyph is literally a complete bird, complete jaguar, complete rabbit, etc. So they are not just symbols.

Full-Figure Hieroglyphs in three Maya Codices Codex Dresden, Codex Madrid and Codex Paris

Posted July 1, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

80% of helpful studies of full-figure Maya hieroglyphs have been on stone sculptures (stelae, lintels, altars, wall panels, etc.) and 20% have found and make available full-figure hieroglyphs on artifacts, especially Maya vases and bowls, found usually in burials and cached offerings. I now add to these helpful studies a comprehensive catalog (inventory, list) of 98% of all full-figure hieroglyphs in the three Maya codices. I estimate that there could be another few glyphs that I missed. Mauricio Moreno kindly sent me two images that I added. Any other examples would be welcomed.

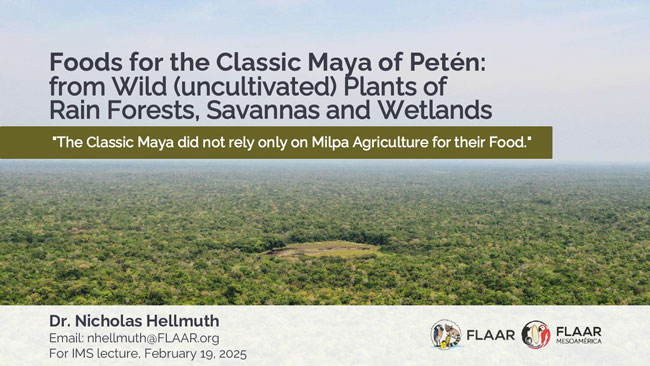

What the Classic Maya actually had available for Food is very different than how Classic Maya Food Sources are presented in Books, Sympsosium Presentations, and Scholarly Articles

Posted February 21, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

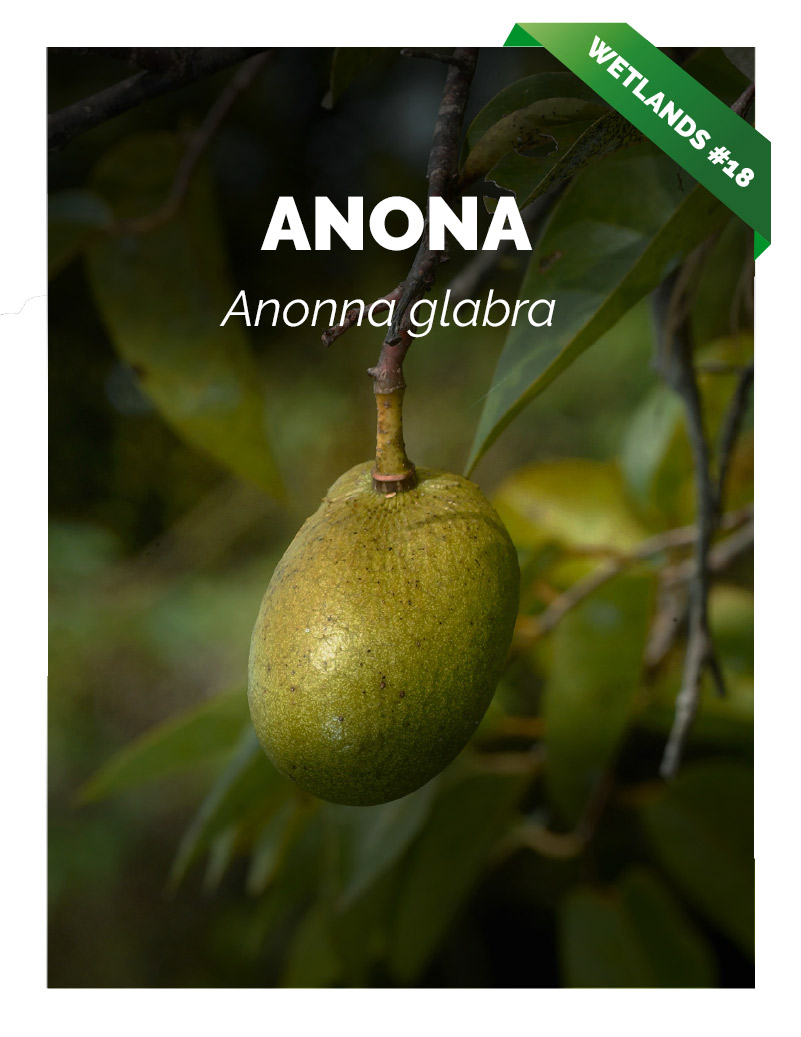

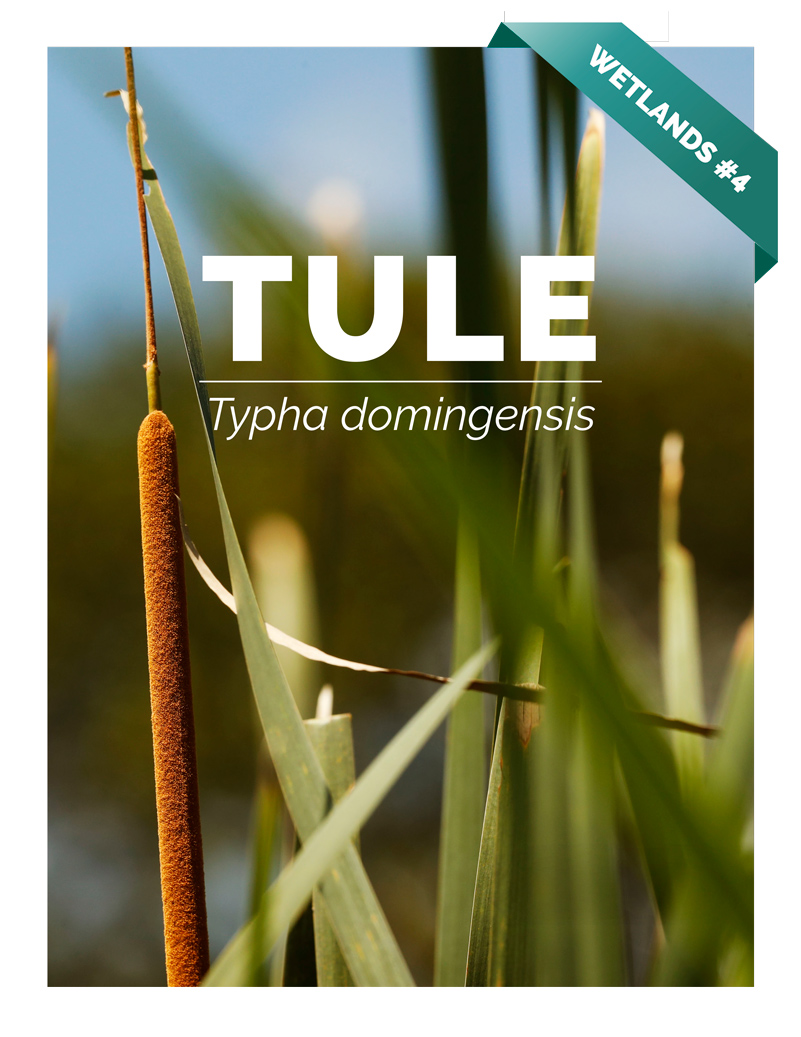

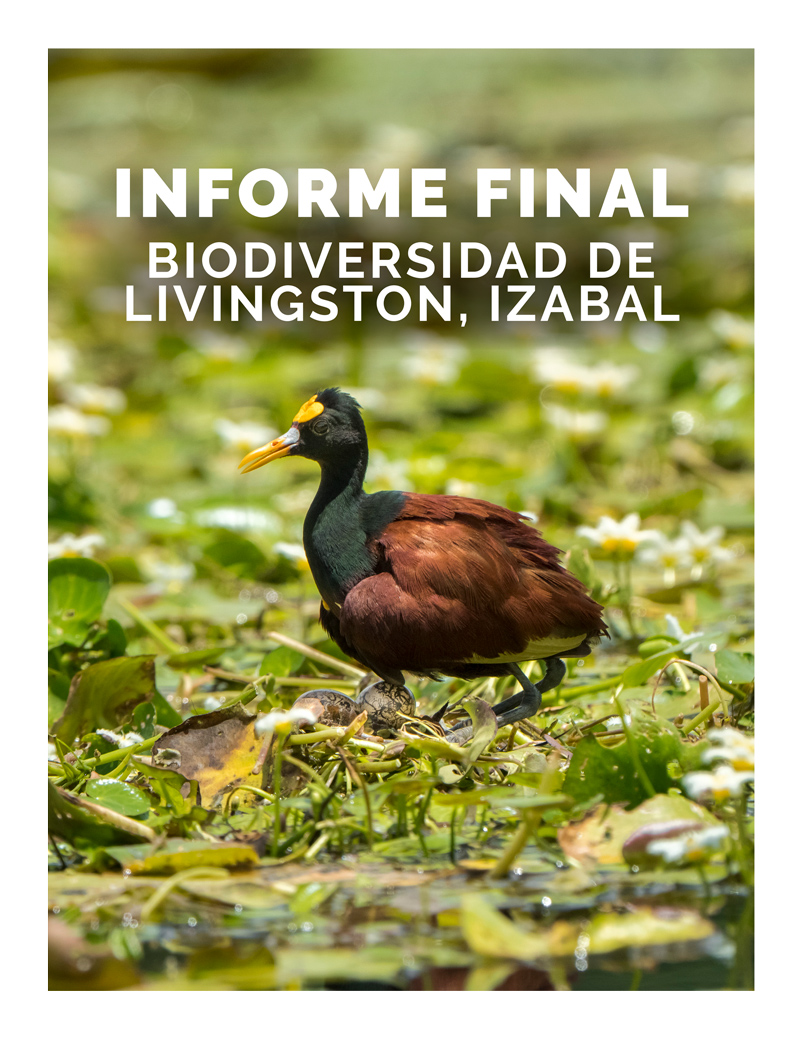

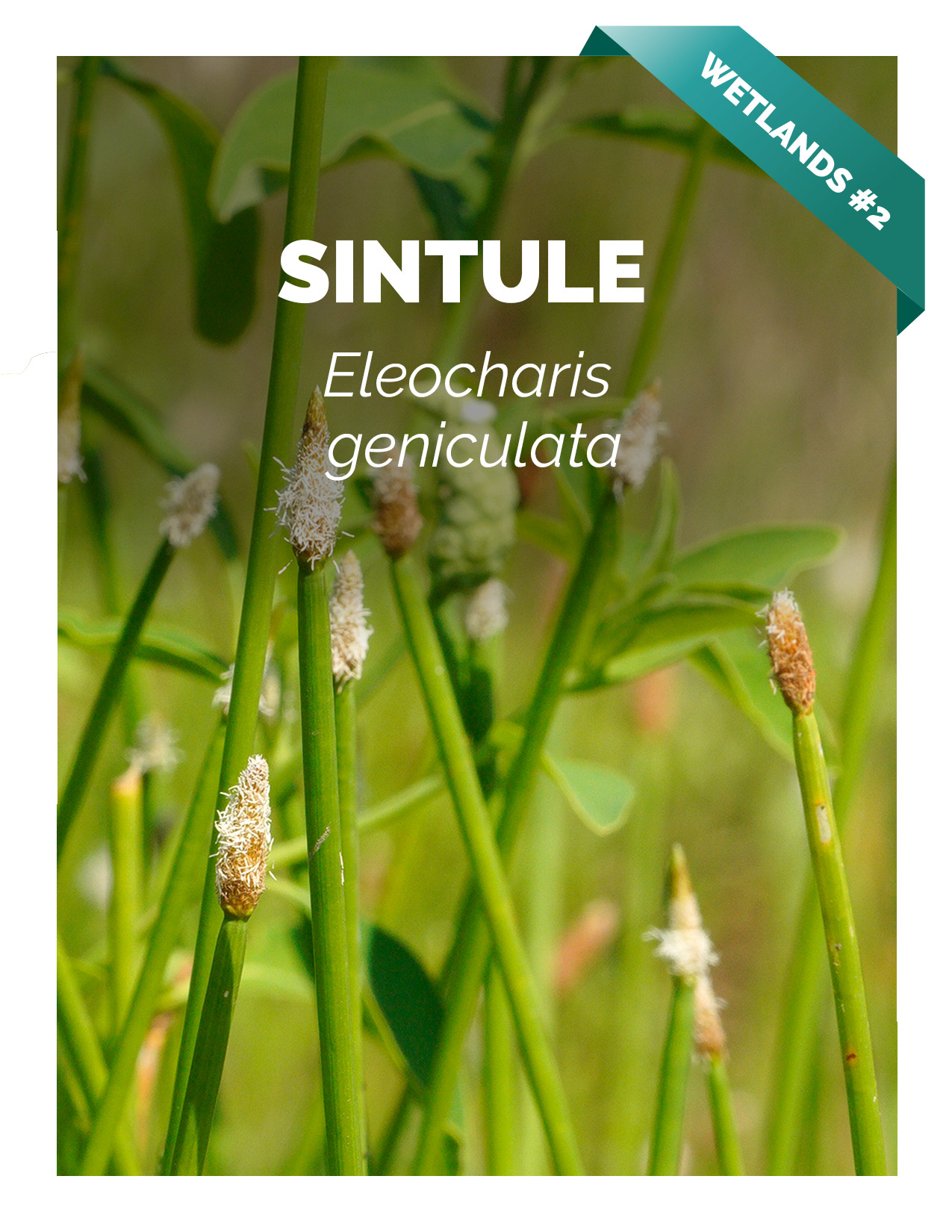

Before the lecture for IMS (Institute for Maya Studies) we showed a preview—now here are the complete 200+ pages of beautiful photos of edible wild plants of savannas of Parque Nacional Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo and Parque Nacional Laguna del Tigre, Peten.

We show the flowers in addition to the actual plants and fruits, and show the swamps and savannas where we found all these edible wild plants during recent six years of field work in remote areas of the Reserva de la Biosfera Maya, RBM.

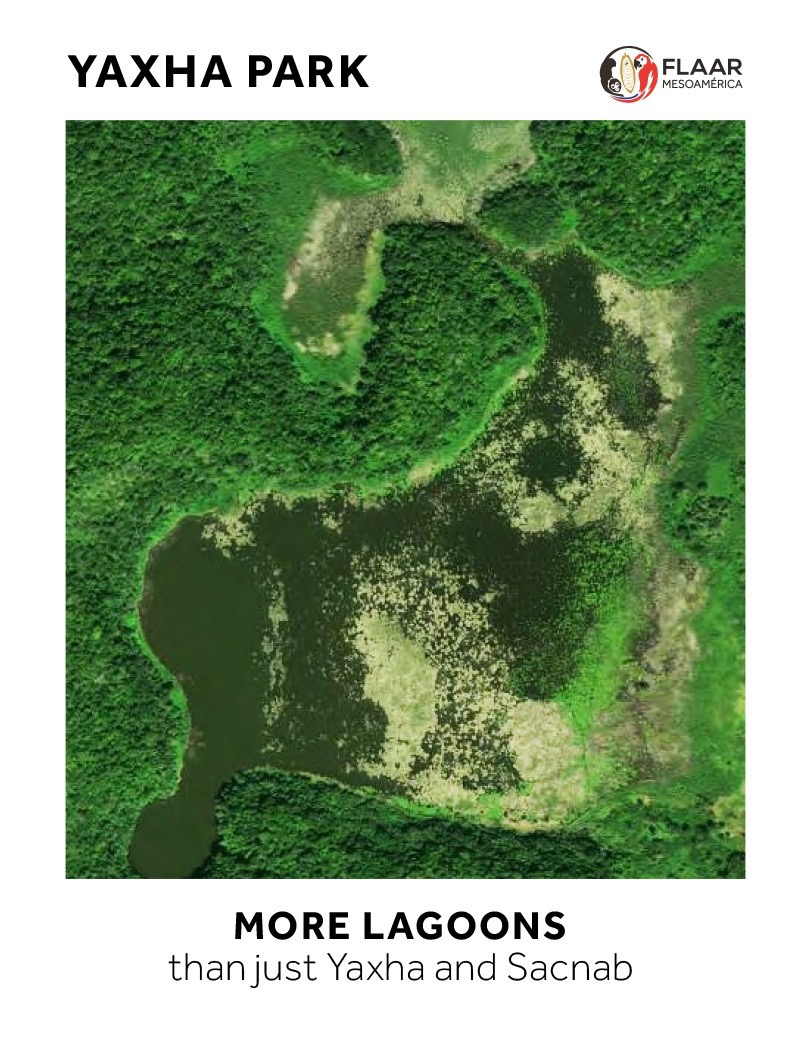

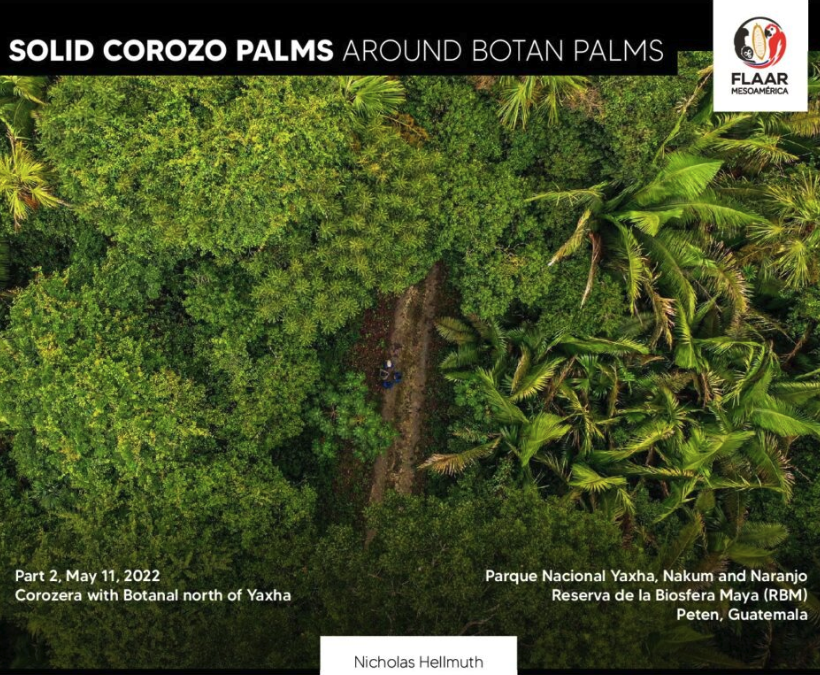

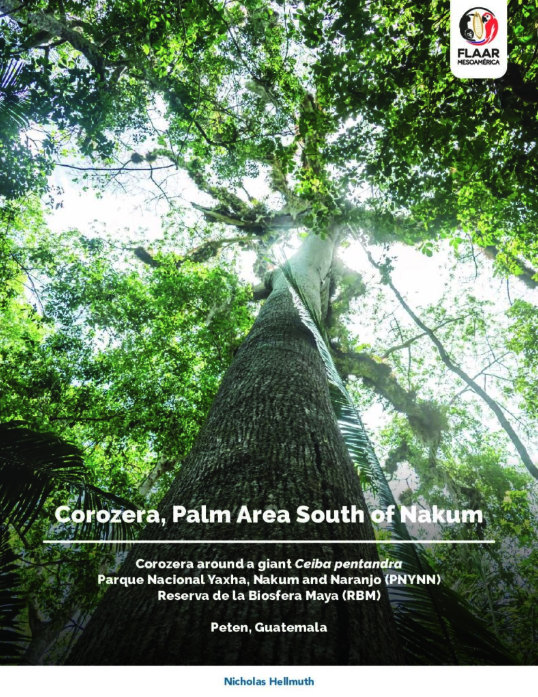

Palm Paradise Peten—“Islands” of Solid Palm Trees in PNYNN

Posted February 18, 2025

by Nicholas Hellmuth

In the 1970’s, while hiking from Yaxha to improve an earlier map of Nakum, the FLAAR team experienced two incredible islands of solid corozo palms so thick with palms that it was amazing. Local people call these a corozera. They are an estimated 80% corozo palm and 10% guano/botan palm—so 90% solid palm trees as far as the eye can see. We have documented the two “palm islands” between Yaxha and Nakum (see below) and now for April 2025 will be hiking to a previously unexplored and undocumented “solid palm jungle area” to the east of the main trail (a corozera that park ranger Teco, Moises Daniel Perez Diaz, told us about recently).

We will also document an escobal/botonal “island” of escoba and botan palms west of Nakum. Then drive through Tikal National Park to reach Uaxactun to explore an amazing corozera south of Uaxactun. We will also document, photograph and map two corozeras adjacent to the Maya ruins of Naranjo-Sa’al. In future field trips, once we have suggestions by park administrators and park rangers at other parks, we wish to document more ecosystems that are solid palms (each about the size of one or two football fields). Most are surrounded by bajo vegetation but the one south of Uaxactun and one at the entrance of Naranjo-Sa’al are partially on karst limestone hills.

Palm Paradise Peten can attract eco-tourists who want to walk through a palm area that no TV documentary has ever shown. Eco-tourism helps encourage to protect fragile ecosystems and provides income for local guides and local hotels.

It would help if a kind soul or foundation could donate the funds so we can purchase a multi-spectral drone—these can map each ecosystem and show from the air the boundary of each “island of palm”. If the helpful individual or family can also donate the cost of a field trip, they can come along and experience the Palm Paradise Peten together with the team of FLAAR (USA) and FLAAR Mesoamerica (Guatemala). This project is part of the 5-year program of cooperation and coordination with CONAP (Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas) and with the administrators of each national park in this Neotropical rain forest area of Guatemala.

If you wish to donate your library on pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and related topics, FLAAR will be glad to receive your library and find a good home for it. Contact:

ReaderService@FLAAR.org