Tasiste in savannas compared and contrasted with tasiste in a tasistal

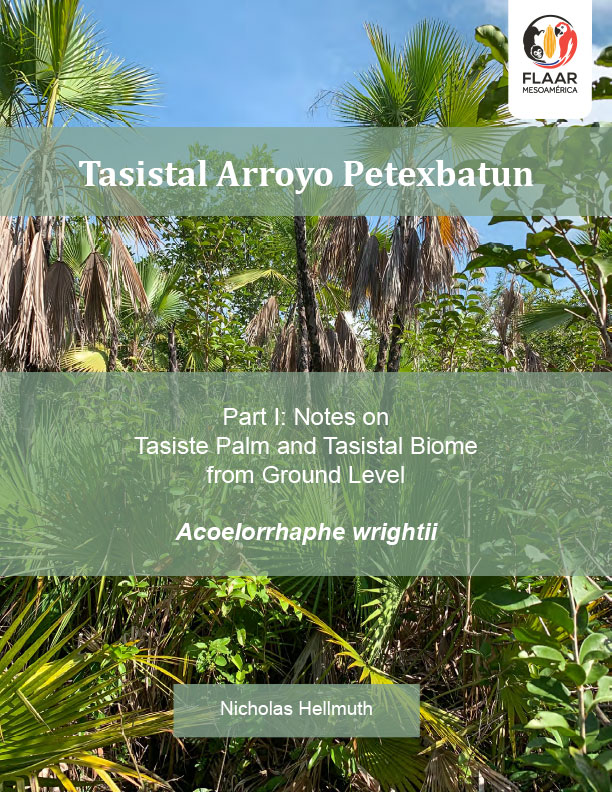

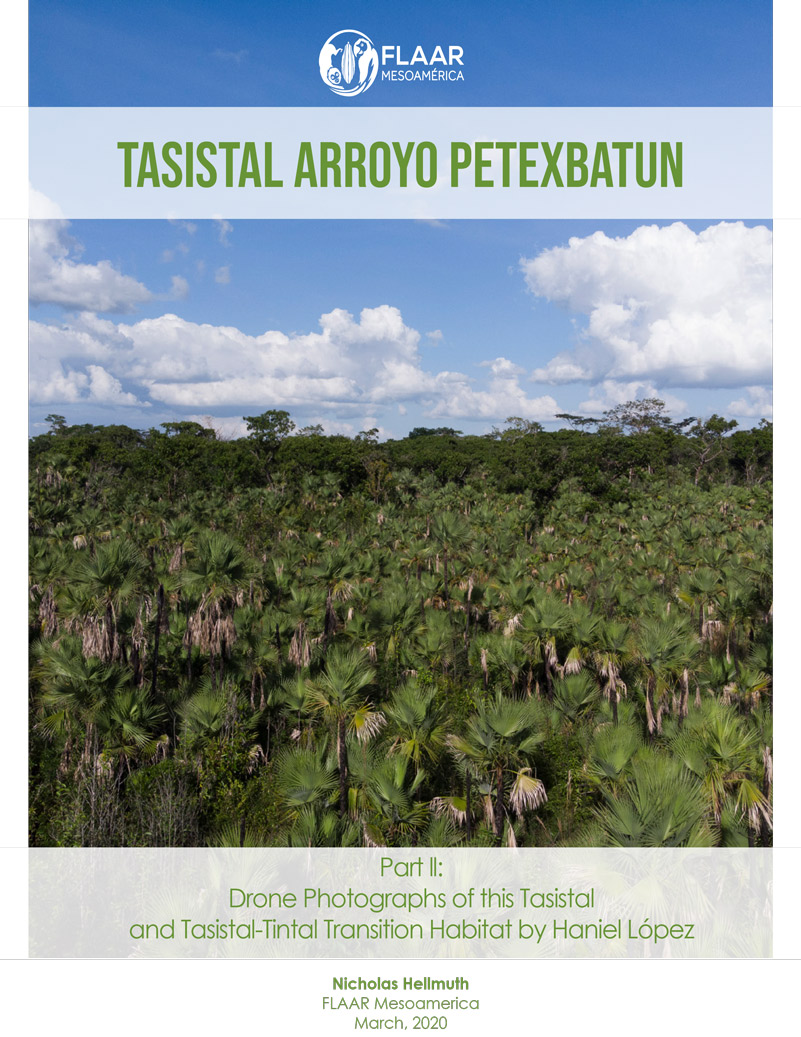

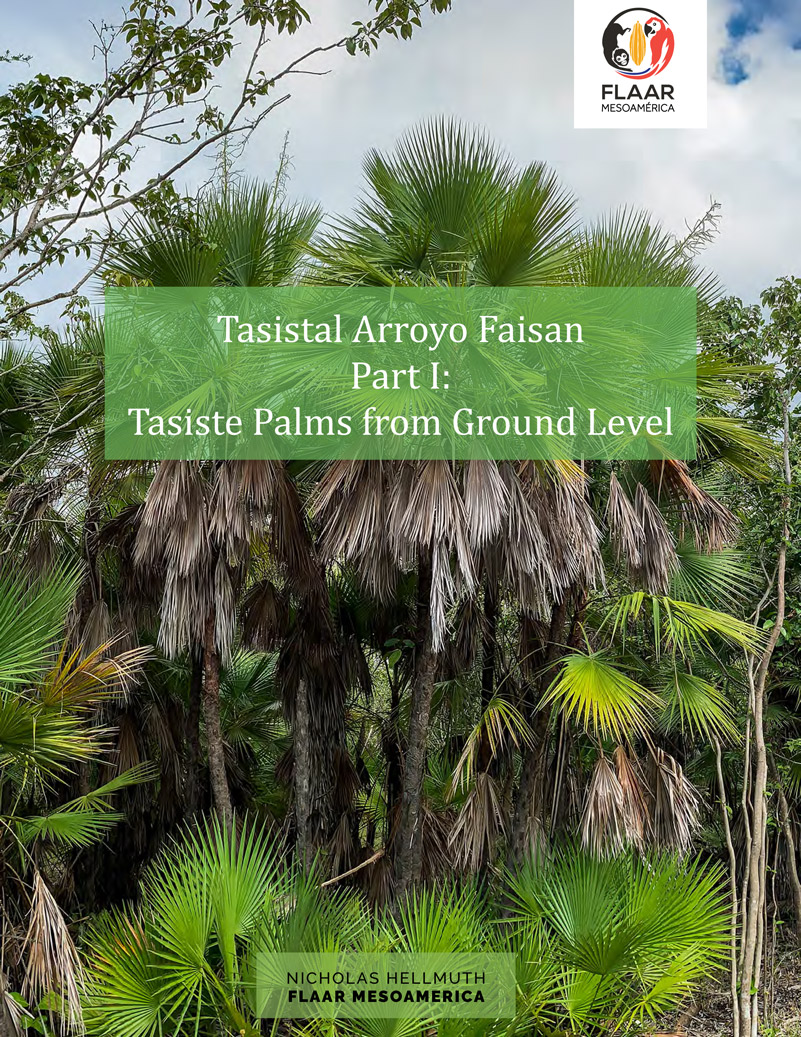

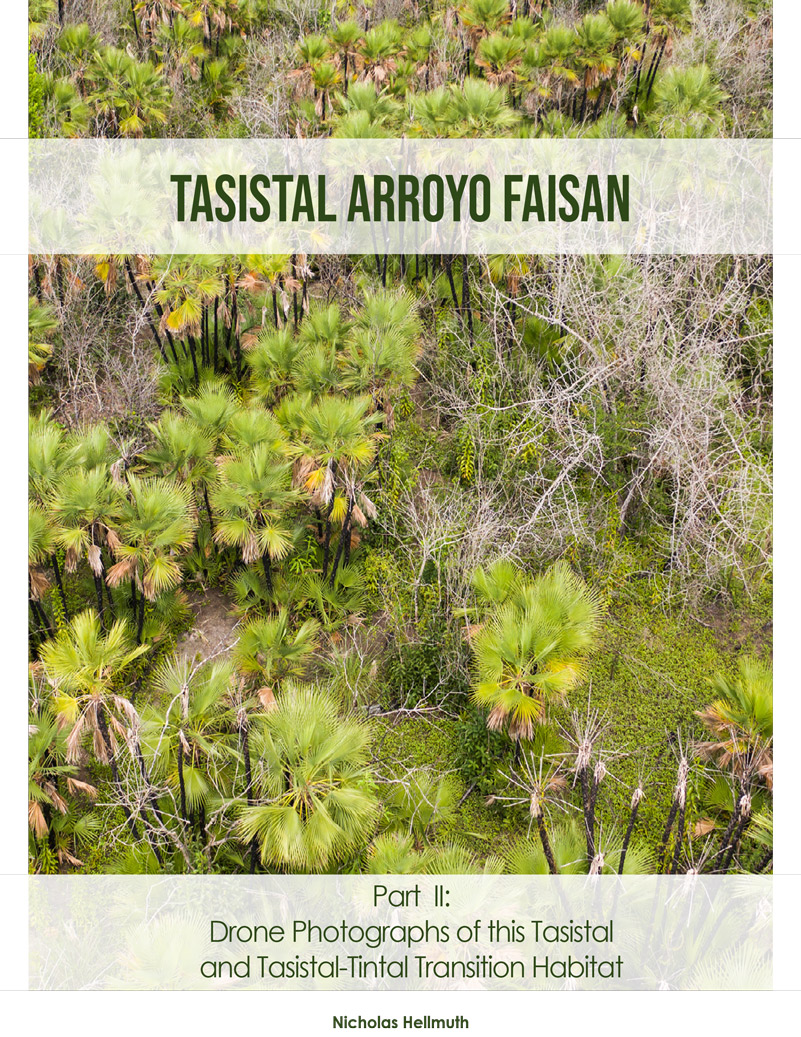

In local (Peten, Guatemalan) Spanish, any savanna with masses of tasiste palms is called a tasistal. Most savannas of Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo, and Arroyo Petexbatun areas are all seasonally inundated in wet years.

|

We estimate about 1 million tasiste palm trees are in this one single Petexbatun area tasistal savanna (estimated 150 to 200 meters wide by 3 to 5 km long). The reason an area of this modest size has so many palms is because this genus and species of palm grows in thick clusters. In a tasistal each cluster is adjacent to the next cluster, resulting in often solid tasiste palm in many areas of a tasistal. But, in other kinds of savannas of Peten, the same palm clusters are much further apart.

In distinction, I estimate less than several hundred tasiste palm trees are in the seasonally inundated Savanna East of Nakum (that we discovered from aerial photos and then hiked 8 hours round trip to reach twice). This grassland savanna is almost one kilometer wide by two or three kilometers long in size. This is the largest savanna discovered so far in Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo (PNYNN). We sincerely appreciate the cooperation of the IDAEH + CONAP co-directors of this biodiverse national park to facilitate our focus on searching for previously undocumented plant habitats. There is no savanna inside or outside the Tikal National Park of this size.

The Savanna of 3 Fern Species I discovered from aerial photos west of Yaxha. With the assistance of IDAEH+CONAP and the friendly local military park guards, we hiked long distances to reach this biodiverse area twice. This previously unlisted and undocumented moist area has only a few dozen or so clusters of tasiste palm (Acoelorrhaphe wrightii, called palmetto palm in Belize and Florida). This is the smallest of the three PNYNN area savannas (but because it is the wettest of the three savannas (in one of the driest of recent years) has plants not present in any of the other savannas in addition to most of the plants of the Savanna East of Nakum).

In the Savanna adjacent to the Naranjo sector of Parque Nacional Yaxha Nakum Naranjo (showed to us by Archaeologist Vilma Fialko and Architect Raul Noriega and with Horacio Palacios as guide) we found at most a dozen or so tasiste palms (if we have the opportunity to study this savanna-cibal ecosystem again perhaps we can find at most a hundred tasiste palms).

So a “savanna with tasiste” and a “tasistal savanna” are two totally different ecosystem terms: again, potentially a MILLION tasiste palms in the one tasistal. All three open savannas of PNYNN have probably fewer than several hundred tasiste palms. Yet the one single tasistal in the Municipio of Sayaxche has potentially over a million individual tasiste palms.

|

|

|

|

|

|

We The tasistal savanna was photographed with an iPhone XS by Nicholas Hellmuth. |

|

If funds become available we would like to physically measure and physically map each savanna. Our interest is to find and document plants in areas other than hilltop vegetation, other than hillside vegetation, and other than bajo tinto vegetation (since all these well known ecosystem types of Peten have been studied for decades). Two of the three savannas in PNYNN and the newly discovered tasistal savanna, have, to our knowledge, never previously been published. The Naranjo area flatland was published as part of the larger Bajo La Pita (nicely shown on a map in a report by Vilma Fialko). Our visit to this area adjacent to the ruins of Naranjo shows that the northern 20% has the bajo vegetation merging into a grassland savanna which then merges into a (not yet botanically defined area) of cibal plus a multitude of tree species which at the north morphs into a more pure cibal area which a few dozen meters further turns into a jimbal (spiny local native bamboo, Guadua longifolia). In other words the northern 20% is totally different than a traditional bajo or tintal of the southern 80%.

It can help archaeologists, ecologists, and other scholars to learn about each distinct kind of ecosystems that were near ancient Maya sites. If agriculture was probably very different 2000 years ago than the slash-and-burn milpa agriculture that is used throughout Mesoamerica today, then potentially the seasonally inundated savannas of Peten surely were utilized by the Classic Maya. This is another reason we are working on making lists of every single plant that is very happy growing in these seasonally inundated flatlands.

We thank archaeologist Vilma Fialko and architect Raul Noriega for teaching us about the flat ecosystem adjacent to Naranjo; we thank Horacio Palacios for guiding us there. We thank IDAEH team at PNYNN (Jose Leonel Ziesse, director, and Lorena Lobos, park biologist; and Mario Vásquez, director of the CONAP team at PNYNN; and park ranger Teco (Moises Daniel Perez Diaz) for locating the trails to facilitate us reaching the Yaxha savanna and the Nakum savanna that I noticed on aerial maps. We thank the photographers and botanists of FLAAR Mesoamerica for their library research, checking the nice herbaria of USAC and UVG, and many weeks of field research. |

How were these savannas used by the Classic Maya?

It would help if ecologists could do scientific analysis here to figure out how the Classic Maya used these flatlands. The obvious questions are: were these areas savannas during the Classic Maya period? And how were these flatlands used by the Classic Maya? As soon as LIDAR is available for the Yaxha, Nakum, Naranjo areas of Peten it should be possible to see to what degree the Classic Maya may have modified parts of at least the progression of bajo-into-savanna-into-cibal-into-jimbal adjacent to Naranjo. For example, Aguada Maya (near Poza Maya three or four kilometers north of Yaxha) is clearly a modified seasonally inundated area, but its modifications by the Classic Maya are obvious: including the fact that it is a rectangle.

Was this tasistal burned every year? Or at least occasionally?

Occasional comments in articles that “the burning of savannas is recent” is highly unlikely because the tasiste palm is the only palm that grows inside a tasistal or inside the other three savannas that FLAAR Mesoamerica has documented. There are corozo palm, guano palm, and occasional huiscoyol palm in forests near and even surrounding most savannas. But, literally, zero of these common palms are inside any of the now four savannas that we have hiked through (three in PNYNN and the new tasistal savanna that far to the southwest and is nowhere (that we yet know of) previously listed or documented).

Tasistal palm root systems are able to send up fresh shoots when it starts to rain after the fire of the earlier dry season. I highly doubt a plant would develop this ability only in recent years. If there was tasiste palm 2000 years ago it most likely was already able to survive fires.

First Posted December 10, 2019