FLAAR Mesoamerica has the honor

to invite you to…

Plantas Comestibles Nutritivas para Mejorar Significativamente la Dieta y Salud de los Niños en las Zonas Rurales de Guatemala

This conference is made to present the importance of nutrition among Guatemalan children, especially in rural areas, and the health benefits that this can have in the Mayan society.

You can download the formal invitation in the link above.

The Search: Rabbit, Hare or Flower?

How to Identify Quatrefoil motifs in Classic Maya art

Full-color, high-resolution presentation

24 July 2014

6:30 pm

La búsqueda: ¿Cómo identificar flores en el arte maya del período Clásico?

Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquín,

6 Calle final, zona 10

Many Late Classic (Tepeu 2) Maya polychrome vases, bowls, and even some El Peten area plates have clear geometric representations of a four-lobed design concept. In 1955 the most experienced Maya ceramic specialist of the Carnegie Institution of Washington called it a “Rabbit Ear” Quatrefoil.

I knew the key Carnegie archaeologists in-person, both Ledyard Smith and Robert Smith, while I was a student at Harvard. They were courteous to a fledgling student. It was kind of academic paradise at Harvard in these years, since Maya architectural historian Tatiana Proskouriakoff was here also. I can still remember her welcoming me into her office in the basement floor area whenever I wandered there.

Dr William Bullard and Dr Gordon Willey were there also (at least one was my Tikal thesis advisor). And there were an equal number of world class Maya ethnographers such as Dr Evon Vogt. I can still remember the comment on my term paper for his class (that I did not yet understand the difference between the Yucatec Lacandon and the earlier Chol(ti) Lacandon). I rewrote the term paper and all the extra reading I did ended up as two of my first publications of my career:

- a bibliography of the Lacandon in KATUNOB

- and an article circa 1977 on Cholti Lacandon agriculture in a book in honor of J. Eric S. Thompson.

This is my style: if I do not at first understand a theme, I do what it takes to correct my initial lack of knowledge.

In effect all my research on the Lacandon was the result of some graduate student assistant to the professor marking my term paper as needing more work. So I gave it more work:

- I went to the main Lacandon research center of Trudy Blom in San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. What resulted was the most complete bibliography on the Lacandon Maya up to that date. No Internet in the 1960’s!

- I went deep into the Peabody Museum Tozzer Library microfilm files at Harvard. Day after day, week after week, to learn more about what in the world was the difference between the Yucatec-speaking Lacandon and the earlier Cholti-speaking Lacandon (they lived in effectively the identical part of Chiapas, around Bonampak, and Rio Usumacinta.

- I then flew to Sevilla, Spain, and worked in the archives read through 17th century handwritten diaries and officla reports on Chiapas and El Peten to discover even more information.

- I did in-depth research in the Archivo General de Central America in Guatemala City to likewise learn more about the Lacandon: both the Yucatec and the Cholti-speaking groups.

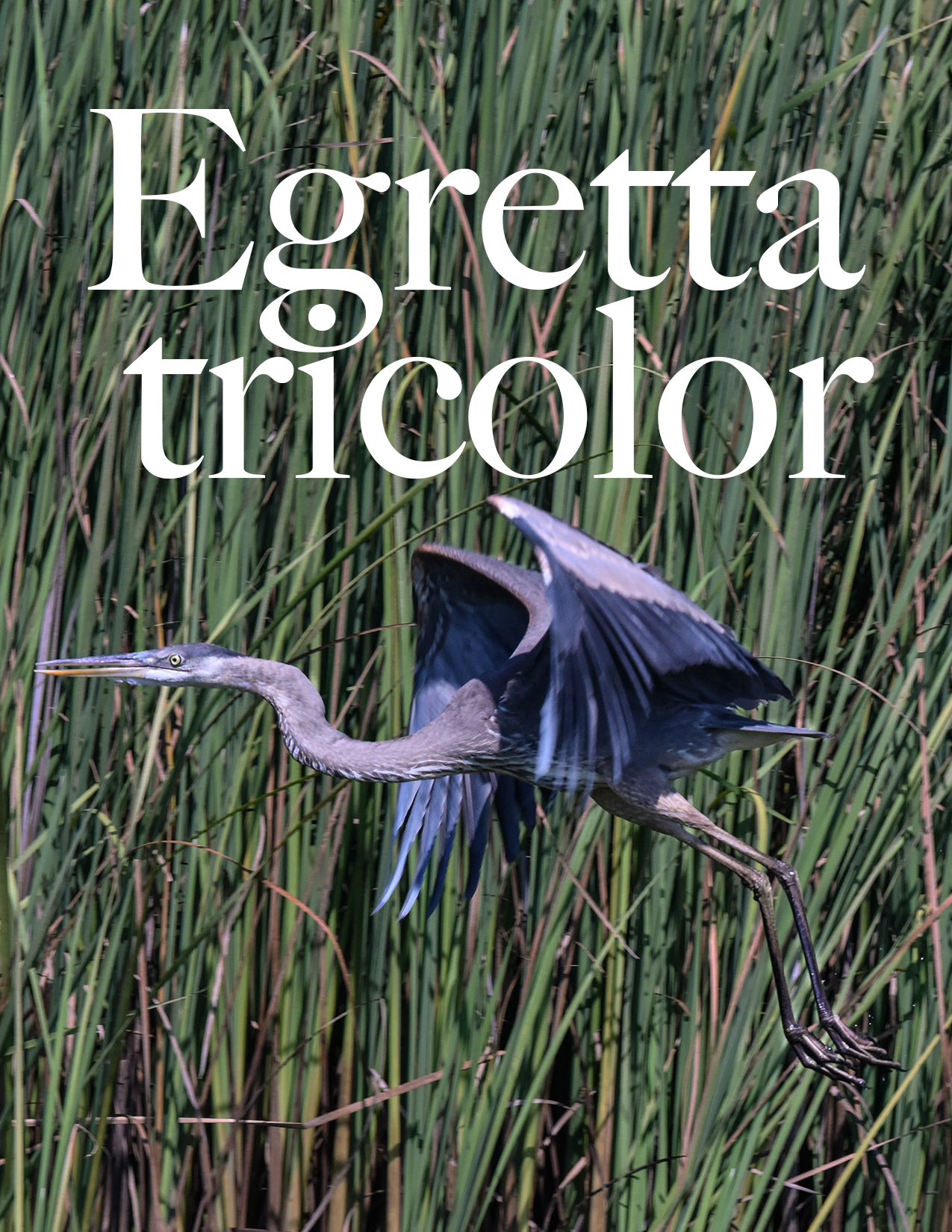

So literally half-way around the world, and research for years. This is my work habit: today I am doing the same with flora and fauna: year after year, going out to the rain forests and swamps. Going into the cages in zoos in Mexico, Honduras, and Guatemala. And building up a sizeable research library on the plants and animals of Mesoamerica.

Actually at age 17 I was already in a Lacandon village and at the same age was already at Bonampak, as a volunteer assistant for a week to the INAH archaeology project of that summer (about 1963). I helped carry things from the airfield through the rain forest to their camp.

My research on flowers of the Maya today is comparable in that I have jumped into flowers 100%. The difference is that I am no longer writing term papers for school work. And no professor (or graduate student assistant) is providing tips and hints of what direction to go to improve my work). Actually I would be hard put to find a Mayanist who is a specialist in flowers other than botanist Charles Zidar (for many years at MOBOT, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis; now he is in Florida establishing a new museum of natural history).

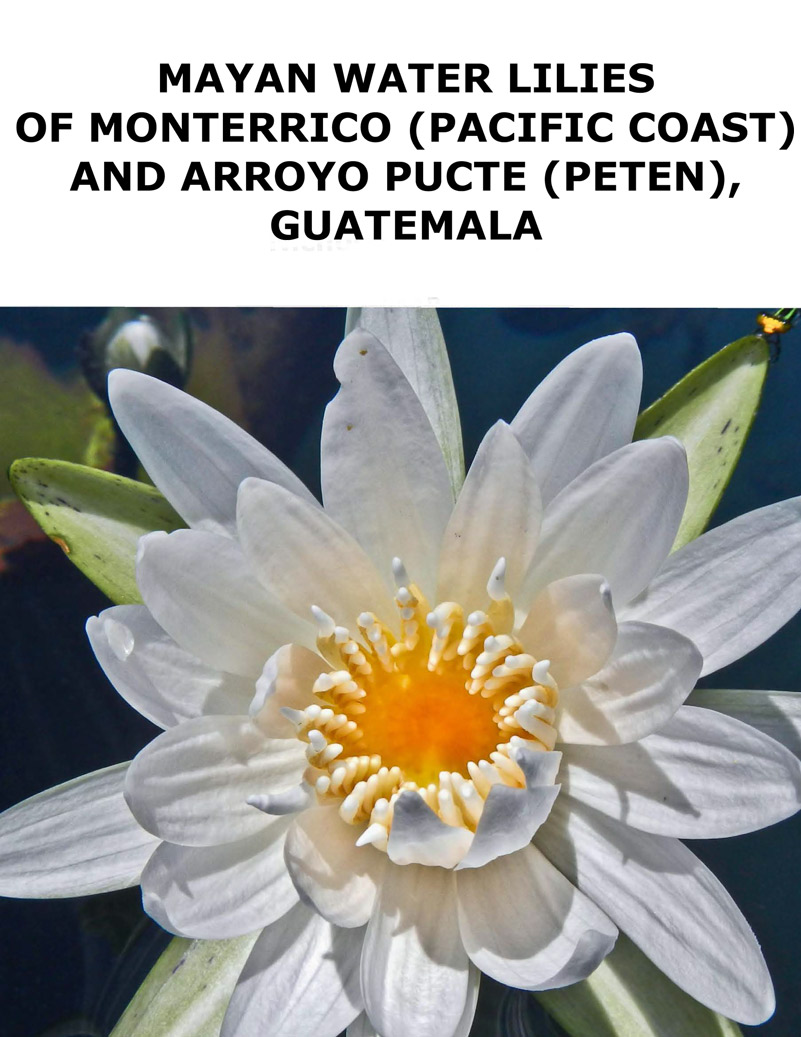

The only paper or lecture I have found so far is by Maddie Brown, 2010. This is excellent, especially if by a student. She covers many different flowers: here in my lecture I will discuss only four-petaled flowers since “all flowers” is the length for a PhD dissertation! Actually water-lily flowers alone could be a complete PhD (this plant was a significant part of my own PhD and I have worked on water-lily flowers since then over five years).

I would consider Dr Karl Taube the most adept at identifying iconographic symbols in general; his strength benefits from the fact that he knows the Aztec, Olmec, and Teotihuacan in addition to the Maya in-depth. Symbolism is “Mesoamerican wide.” Rarely is a symbol or a concept limited only to the Maya.

Thus it is worth noting that when I sent Charles Zidar my notes on 4-petaled flowers he replied that it was specifically 4-petaled flowers that he had not been able to identify at all. In his over decade of botanical research: no discovery of a 4-petaled flower.

In my own research: the same: over a decade and I never noticed any scholarly discussion of 4-petaled flowers. Ironically some of the Peten representations looked like an arrangement of four conical shells (sort of Oliva-like). Surely there must be a student paper or an article by an epigrapher or iconographer somewhere, but I have not yet found one (keep in mind that most of my time is deep in swamps near Monterrico, in swamps off the Rio de la Pasion, or in fields, deep in forests, or high in mountains. We hike for miles with tons of photography equipment to record these flowers (since they are being bulldozed, burned, and otherwise totally destroyed in the rush to make money out of the land).

Are these designs a set of rabbit ears?

Although the Tikal project archaeologist T. Patrick Culbert gives no iconographic commentary whatsoever on the four-segmented designs on the bowls and vases of Late Classic Tikal, already by 1955 this design was called the “Rabbit Ear” Quatrefoil by the Carnegie Institution of Washington and simultaneously Harvard ceramic expert Robert Smith.

Robert Smith was a graduate of Harvard plus he did lots of field work at Uaxactun, Mayapan and other Maya sites in Mesoamerica. He and his brother Ledyard Smith were always hospitable to me when I wandered into their offices (I was an undergraduate student at Harvard, circa 1962-1967 (I was at Harvard over a 5-year period, having taken 12 months off before my junior year to live and work at Tikal for the University of Pennsyvalnia; taking “a year off” was traditional during the 1960’s).

So, if a known Maya specialist suggests RABBIT EARS, then let’s look at the ears of rabbits.

The authoritative Wildlife of Mexico, by A. Starker Leopold, Fig. 128 shows

- four species of cottontail rabbits

- Two other rabbits

- Two jackrabbits (“hares”, liebres in Spanish).

Of these species, it is the jackrabbits (hares) which have ears closest to the design on the Uaxactun vases and bowls.

Yet only one single rabbit is mentioned in Animals and the Maya in Southeast Mexico (Anderson and Medina 2005:146).

Not one single solitary rabbit or hare is pictured in “Animals & Plants of the Ancient Maya,” rather a surprise considering this book is published by the University of Texas Press (and is used as a major textbook for endless courses on the Maya across the USA and Canada).

Wikipedia lists only two rabbits and zero hares for Guatemala:

- Tapeti Sylvilagus brasiliensis

- Eastern Cottontail Sylvilagus floridanus

In preparation for this lecture I Googled “Hare” “Guatemala” and so far have not found a single native species of hare for Guatemala.

In other words, there do not seem to be any hares native to Guatemala, and especially not to the Tikal area. And during the 12 months I have lived in Tikal and five seasons at Yaxha, I definitely did not notice many rabbits (though surely they exist; but are more common along the dry Rio Motagua area of Guatemala).

So I conclude that it is unlikely that the designs on the Uaxactun vases or bowls are rabbit years or the ears of hares either.

So what is the symbolism of these rounded shapes?

It is rather obvious that this geometric design represents some kind of flower.

But what species?

I must admit in the over 40 years that I have been studying the designs on these Tikal tomb ceramics, I have never once even dreamt of them being rabbit ears. But since an experienced Mayanists suggested rabbit ears, I needed to devote the time and research to understand what chance of rabbits being the source for this design.

My conclusion: sorry, these are unlikely rabbit ears.

While discovering the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar at Tikal (while a student at Harvard, at age 19), I found many paintings of these 4-petaled designs in this royal crypt. Yet 49 years later, no iconographer, epigrapher, archaeologist, or ethnobotanist has identified this 4-petaled design (or if so, I apologize that I have not yet noticed their article). Indeed I asked a PhD candidate who is doing an excellent dissertation on sacred Maya flowers, and he told me that he had not yet found the actual species with these specific flowers.

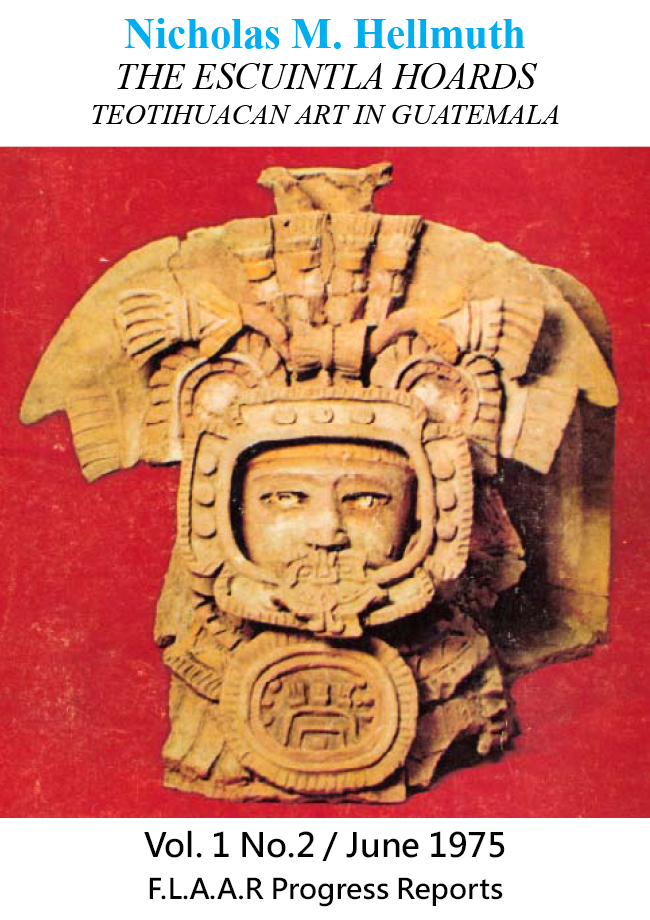

This Maya flower is quite different from 4-petaled flowers of Teotihuacan.

Whether this 4-petaled flower is related to the Kin (Sun) hieroglyph will require a major research project to sort out, since J. Eric S. Thompson and too many writers on Lacandon Maya ethnobotany have not fully understand the actual flowers of the Maya fields and forests.

Thompson, and most linguists, have (mis)identified the Kin glyph as being based on Plumeria (Flor de Mayo). This is a mis-identification even more serious than calling the impressive insects on Late Classic Tepeu Peten ceramics “cockroaches” when they are potentially lightning bugs (fireflies) as clearly mentioned in the Popol Vuh. Potential mis-identifications of centipedes join the list of unfortunate examples of how library research 5000 or 15,000 km from actual centipedes ends up with misunderstanding the actual structure of each flower or creature.

Finding an actual 4-peteled flower anywhere in the world is a challenge: most flowers have five, or eight, or more petals. Even 3-petaled flowers are more common than 4-petaled flowers.

But finding 4-petaled flowers in botanical monographs is actually part of the problem: it is not just the flower which counts, it is the eco-system where the flower is pertinent. To understand the eco-system you have to experience it in-person; you can’t adequately do this in a library.

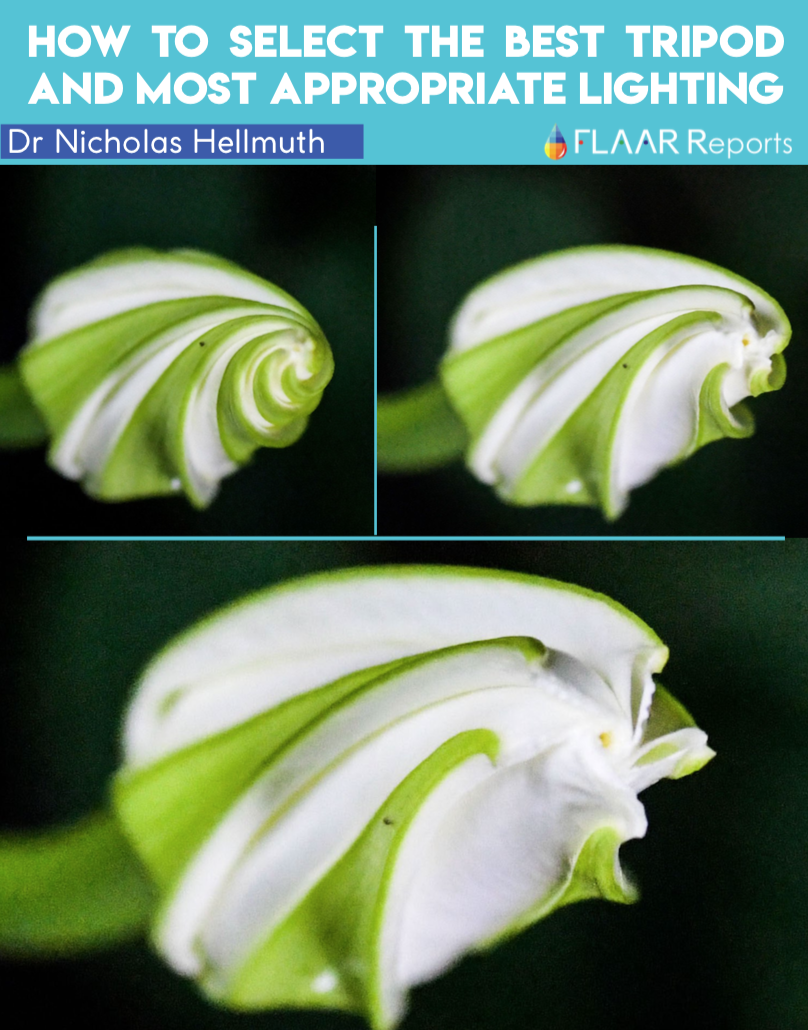

So this presentation at the Museo Popol Vuh, Universidad Francisco Marroquin, will cover the actual physical search (for years) out in fields and forests of Mesoamerica.

Has the 4-peteled flower been found? What if the Late Classic Maya design is really a leaf with four sections!

If 4-petaled species (flowers or leaves) have been found, how do we know which species is the actual prototype for the Maya polychrome paintings on ceramics?

|

Is this 4-lobed flower symbol a Maya development? Or did the Maya evolve their designs from 4-petaled flowers introduced by the Teotihuacan merchants and missionaries during the 4th-6th centuries.

So we hope to see you at the MPV lecture room, on the hospitable campus of the impressive UFM to see high-resolution photographs.

If you love flowers (and leafy plants, since what if this is a leaf?), if you like the outdoors, if you are curious how we get such high-resolution photographs? You are also welcome.

Although this lecture is for students of iconography, epigraphy, botany, biology, archaeology, ethnography, and linguistics, it is also a good opportunity to learn tips on sophisticated techniques of both studio photography and field photography of flowers.

Posted July 2014, the week of the lecture at the Museo Popol Vuh, Guatemala City.