To the Maya priests and kings two thousand years ago, each of the world directions had its own color. Color was used to paint murals and entire pyramids and palaces: most Maya buildings were painted red. So to study Mayan archaeology, ethnography and especially most artifacts, you run into color pretty quickly. The Maya colored even their cacao: it was not chocolate color but red, from achiote. And pre-Columbian chocolate drink was not as sweet as ours, but rather bitter, especially when seasoned with chile!

So if you study Mayan anthropology, or archaeology, sooner or later you will run into colors. What is also impressive is that colors on Maya murals and pottery last thousands of years. Yet modern colors on inkjet printers, if dye inks, the colors last only a few months in the sun and only a few years inside. Even pigmented inkjet colors last at most three to five years outside. The claims of 200 year longevity is an advertising ploy: not many modern chemical colors last more than a few years on inkjet materials. The 200 year longevity is if kept inside a dark chamber that is purified from most of the common pollutants that float around in our modern world today.

So many pre-Columbian colorants used by the Maya, Teotihuacan, Zapotec, Classic Veracruz, Toltec, and Aztec last longer than modern chemical colors.

Colorants for the Classic Maya by what was being colored:

-

Food coloring from plant materials: the best example is achiote

-

Food coloring from animal materials (insects): Cochineal

-

Colorants from seashells: several species of Pacific Ocean shells

-

Colorants from tree sap: Croton

-

Colorants from trees: Palo de Brazil, Palo de Campeche, añil, Indigofera suffruticosa, chooj; mira, Chlorophora tinctoria; Pericon, Tagets lucida

-

Colorants for Maya architecture: special kinds of clay and other colorants

-

Colorants for Maya murals: diverse clays, minerals

-

Colorants for the famous “Maya blue:” palygorskite

-

This is not intended to be a complete list, but is a start.

|

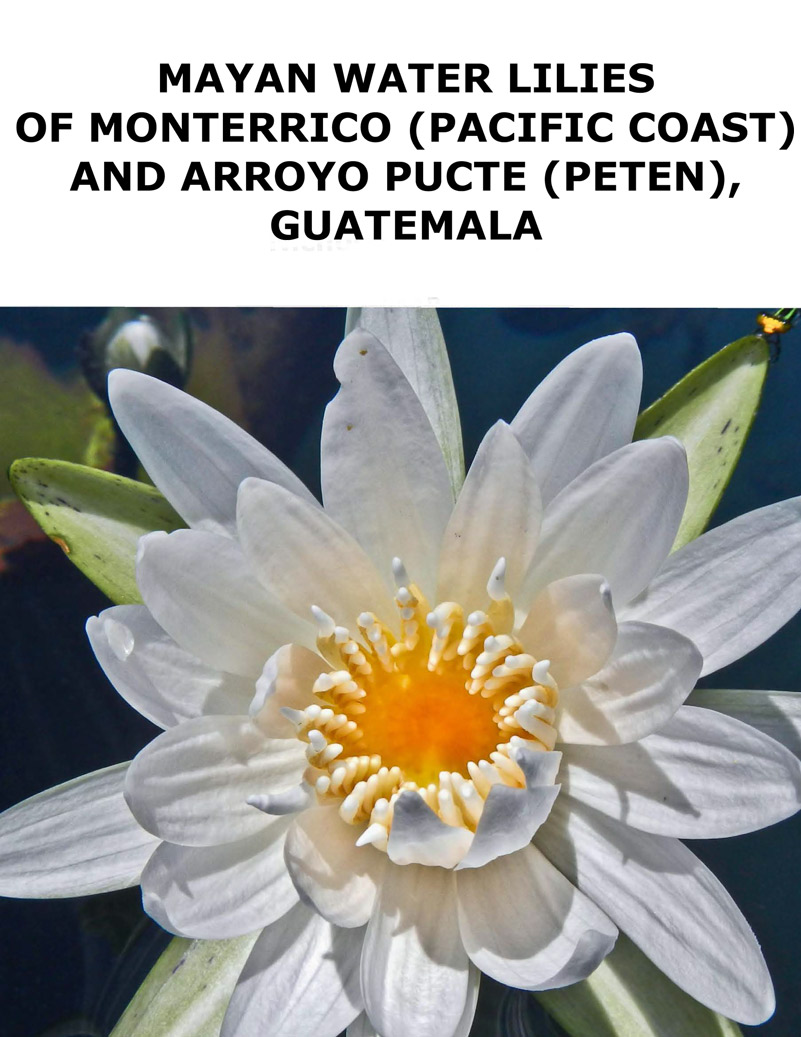

Achiote Bixa Orellana is best known as the source of the natural pigment annatto, produced from the fruit.

|

Colorants used by the Maya came from diverse sources

-

Colorants from plants: achiote, indigo, añil and many more

-

Seashell pigments for purple

-

Insect pigments: cochineal

-

Mineral pigments: palygorskite, cinnabar, hematite

-

Probably the most common colorants are from clays, minerals, and plants. When a local area lacked the colors they needed they obtained the colorants from trade.

-

Caves would have been a source of some Maya colorants, especially clays. Plus other minerals and stones would have been obtained by the Maya inside caves to use in making small stone sculptures.

Books on colorants for Maya art and archaeology

HOUSTON, Stephen, Claudia Brittenham, Cassandra MESICK, Alexandre TOKOVINNE, and Christina WARINNER

2009 Veiled Brightness A History of Ancient Maya Color.

PONTON ZUNIGA, Raul

Tintoreria Mexicana: colorantes naturales. Estado de Mexico. 181 pages, excellent, but has no index, no glossary, and zero bibliography.

One book we recently stumbled over was “Cave Minerals of the World,” by Carol A. Hill, co-authored by Paolo Forti. His website mentions palygorskite clay as one of the origins of the Maya Blue colorants. Many articles cover this subject as well. Maya blue is a long-lasting pigment used especially in Classic and Post Classic wall paintings on Maya palaces and temples.

Arnold, Dean E. 2005 Maya blue and palygorskite: A second possible pre-Columbian source. Ancient Mesoamerica 16(1):51-62.

Arnold, Dean E., Jason R. Branden, Patrick Ryan Williams, Gary M. Feinman and J.P. Brown. 2008. The first direct evidence for the production of Maya Blue: Rediscovery of a technology. Antiquity 82:151-164.

Arnold, Dean E., Hector Neff, Michael D. Glascock, and Robert J. Speakman. 2007. Sourcing the Palygorskite Used in Maya Blue: A Pilot Study Comparing the Results of INAA and LA-ICP-MS. Latin American Antiquity 18(1):44–58.

Berke, Heinz 2007 The invention of blue and purple pigments in ancient times. Chemical Society Reviews 36:15–30.

In the library of Na Bolom, San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico, about 20-something years ago, I vaguely remember a book or books on pigments for dying Maya cloth for indigenous weaving. Balam would be the normal way of spelling jaguar in Mayan languages.

FLAAR interest in colorants

Our goal as an institute dedicated to Mesoamerican studies of Latin America is to make available information as it becomes known to us. In the past we have engaged primarily on studies of Mayan ethnobotany and ethnozoology related to Mayan iconography of symbolism in murals and on funerary pottery. But since there were many colorants in the Tomb of the Jade Jaguar that I excavated at Tikal in 1965, I am interested in finding the sources of these colorants. Another reason for working on colorants is that many of the trees and plants that FLAAR is already studying are sources of colorants. Once I have a list of colorants from leaves, sap, and bark, I have an interest in learning what colorants are available from clays and minerals.

And of course the most infamous colorant of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica is the insect cochineal. This insect color is still used all around the world today.

Sources of information on colorants used by the Maya

I first learned about colorants at age 19 while excavating for the University of Pennsylvania in 1965 at Tikal. The royal burial that I discovered was filled with red colorants, primarily hematite and cinnabar. There was not really any specialist on minerals readily available on site at that time. Most of the good geological studies have been directed towards obsidian. Most geological studies in the last decades have been on Belize, not Guatemala. For example, I have not yet found a geologist who can tell me where the Classic Maya obtained their cinnibar.

My first documentation on Maya colorants came from my research in the Archivo General de las Indias, Sevilla, Spain (1971). There I discovered Spanish records of their conquest of Sac Balam, a village of the Cholti Lacandon (the original inhabitants of this part of Chiapas, before the Yucateco speaking Lacandon Maya arrived later). The Spanish spoke of the black charcoal that the Cholti Lacandon used.

Updated July 7, 2009

First posted January 2009.